by blogadmin | Dec 15, 2018 | Blog Post, India, Punjabi Story, Year 2018

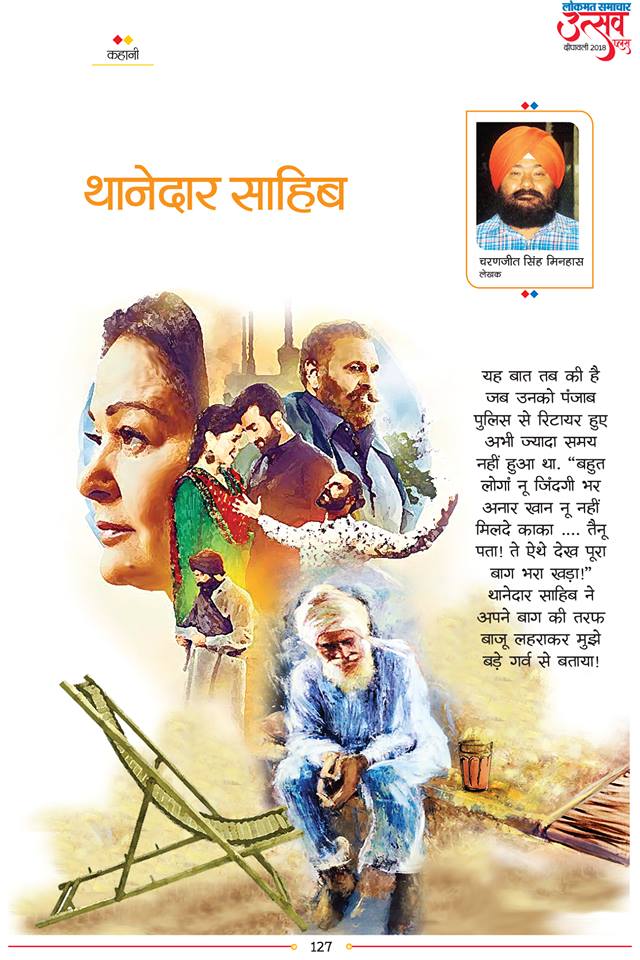

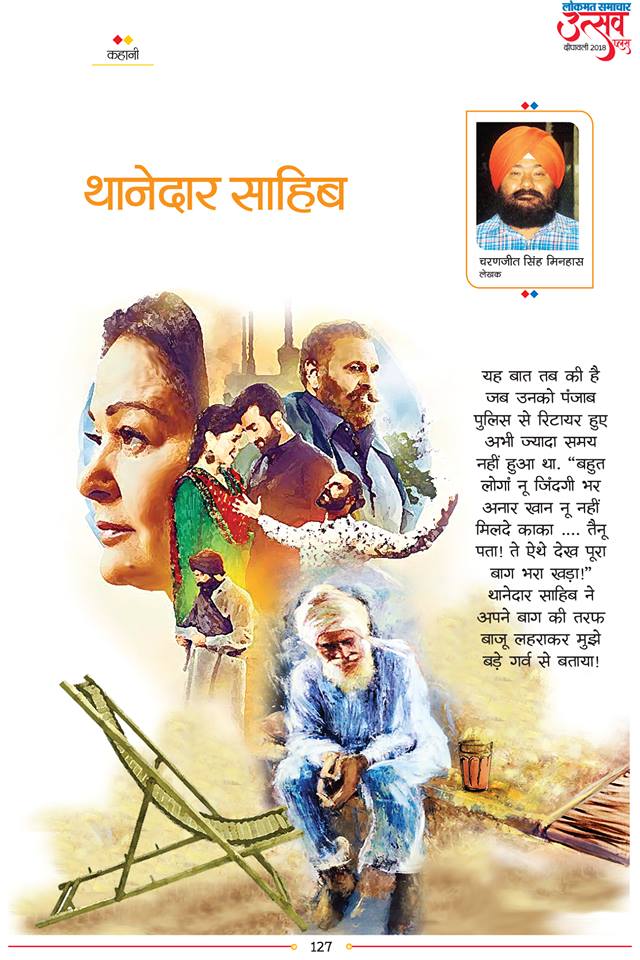

I originally wrote this story in Punjabi a few years back. Its English translation was published by Atlantis last year. This year, Lokmat Samachar, included its Hindi translation in its annual Diwali Ank. My first work published in three languages. I am happy, thankful and inspired to continue to better my writing.

by blogadmin | Dec 11, 2018 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Sikhism, Year 2018

It was the morning of the Thursday (15 November) before — one full week before Turkey Day, an informal way we here in America refer to Thanksgiving. It was snowing outside. Delaware National Guard’s 36th Annual Prayer Breakfast was that same morning, and I was among the invited.

Like a pucca Indian, when I reached the venue, Cavaliers Country Club, others were about to finish eating. I was courteously led to my designated table after I showed the reception staff my driver’s license to help them out of the struggle with my name.

My friends, (Rev.) Tom Davis and Jack Sanders, got up to give me a hug. Among the others at the same table was Chaplain (Lt Col) Andy Werner, who I later learnt had started this wonderful tradition. He had paid for my breakfast, too. I blessed him even more for that.

In the large hall were men and women in uniform and, of course, the chaplains, most of them in uniform as well, making me wonder if their divine approach was any different from their civilian counterparts.

The woman who came to greet us at the table was the Adjutant General, the official host of the event.

The woman who came to greet us at the table was the Adjutant General, the official host of the event.

The woman who came to greet us at the table was the Adjutant General, the official host of the event. The only other person I could recognise was Delaware Governor John Carney when he greeted me. We were later informed that representatives of the state’s Congressional delegation were there too.

Driving back, I wondered about the various ways Americans celebrate Thanksgiving. Some start with a great breakfast followed by an evening feast of turkey, cranberry sauce and green bean casserole.

In India and most other countries, such joyous feasting and festivity is reserved for religious events. But this great American festival is for everyone, including those who have no faith or don’t believe in Rab-ji! (God).

Here, we have had our own tradition since 1992. People of different religions in our area come together at an inter-faith Thanksgiving prayer. Clergy members (I am an exception) of different faiths and denominations speak at the event. More than two hundred people attend year after year.

I have been associated with this great tradition from several years. It started when I first attended one of the group’s monthly meetings as a representative of the local Sikh community.

Members of the group have joined me in the last two inter-faith peace walks as part of the Delaware Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month. The Delaware Sikh Awareness Coalition (DSAC) — which I founded and chair — organised the DSAAM resolutions as well as the peace walks in April of 2017 and 2018.

The DSAC also has received tremendous help and support from Rev Cynthia Robinson (my dear “sister”) of the New Ark United Church of Christ. She even knows a couple of Hindi words, learned from her aunt who was a missionary in India — including Batala in Punjab — for several years. One of them is shabash,which Cynthia not only uses appropriately but wonderfully.

Last year, when I shared with fellow speakers and the audience why Thanksgiving has this special connection for me, I was mobbed at the end by people to further explain to them the grand idiom of positivity and prosperity — Sarbat Da Bhala!

I told them that every Sikh prayer I had ever heard or read ended with Sarbat Da Bhala, regardless of the occasion, day or time. However, I considered it a religious formality without real life application.

Then I came to America and experienced Thanksgiving. That’s when the bulb in my mind lit up and I understood, for the first time, that the spirit of Sarbat Da Bhalaalso has practical applications in real life. The native Americans didn’t help the pilgrims because they spoke the same language or had the same colour or because their religions were the same.

And they certainly did not support the same cricket team, nor did their wives belong to the same kitty group. I am sure their kids didn’t go to the same high school, I told them. For me it was simply a living example of Sarbat Da Bhala! It was the embodiment of the divine saying.

And so, I am sure my “sister” Cynthia will not mind when I borrow her word to say, “Shabash Thanksgiving!”

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.thequint.com on Dec 01, 2018 & www.delawareonline.com on Dec 10, 2018.

by blogadmin | Nov 12, 2018 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Year 2018

It was the Saturday after — the first Shabbat service in the aftermath of the Pittsburgh tragedy was about to begin.

Sunmeet Singh Sethi and I entered the local synagogue here in Newark, Delaware. Rabbi Jacob Lieberman, a short, handsome man wearing a kippah, like many others in the congregation, stepped off the dais to welcome us.

After returning to the lectern, the rabbi’s hands rose repeatedly to clean his cheeks. Then he left.

I noticed other congregants turning their necks to look at us with grace and kindness. He reentered after a couple of minutes and looked at us and others. He was still crying.

Growing up in Punjab and studying and working in India, America to me, and those around me, was a mecca of creative and constructive activities — a land of opportunities. No wonder, then, that an army havaldar’s son could dare think of starting a software company immediately after landing here in 1999.

Related: Pittsburgh shooting is a blow against the very soul of America

A 97-year-old, an elderly wife and husband: These are the 11 victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre

That company, Tekstrom, will celebrate its 20th birthday next May.

Even the sky wasn’t the limit in America, or so we all believed. Americans had literally proven it by landing on the moon a year before I was born.

The assembly line, harnessing the atom, developing the computer and creating the cyber age — America had revolutionized the world on many fronts.

For someone who dreamed of coming to this country, and worked hard to make it happen, it has been especially painful to witness the hatred expressed by a tiny, but lethal, group of individuals in this country.

Six years ago, it struck a gurdwara in Oak Creek. Recently, a synagogue in Pittsburgh. In between, a black church in Charleston.

All three tragedies were perpetrated by lone white supremacists; all three at places of God; all three at an interval of three years.

In each case, the perpetrators’ numbers rose: six victims the first time; nine the second; and 11 in Pittsburgh. And, then there were the additional tragedies in schools across the country, the concert in Las Vegas, the nightclub in Florida, among others.

Sunmeet and I were at Temple Beth El to express our love and solidarity with the Jewish community. We were there to share their unspeakable grief that resulted from the unconscionable desecration that occurred the preceding Saturday.

The sinking feeling I had after hearing about the Oak Creek shooting is still fresh with me. I was in Bangalore that day visiting my India operations with my wife and two children. Renu and I were worried especially about our son. He was then, and even today, the lone Sikh boy with long hair to ever attend his private school in its century-old history.

Every Saturday he has a private lesson with his violin teacher at her house, a place my family knows well from the many Passover dinners we’ve enjoyed there. That day I dropped my son off for his Saturday lesson and went to the gym.

It was there, on the wall-mounted TV-screens, that I learned of the tragic Pittsburgh shooting. It triggered that familiar sinking feeling once again. I thought of my Jewish friends and their pain and anguish.

The next day I joined hundreds of others gathered at a vigil on the steps of Memorial Hall at the University of Delaware in Newark. We had assembled to express our solid rejection of the anti-Semitic hatred that infected the shooter who wanted to “kill all Jews.”

Addressing the gathering, which included representatives of many faiths, Rabbi Lieberman had this to say: “For our grief, this is an opportunity to mourn. For our outrage, it’s a time to cry out. For our fear, an opportunity to pray and to invite courage, and for our vulnerability, it’s a time to stand with others and to discover that we are not really alone.”

Others spoke as well. “Today, we are not Catholic, Protestant, Buddhist, Muslim [or] Hindu,” U.S. Senator Tom Carper said. “Today, we are all Jewish.”

Delaware Congresswoman Lisa Blunt Rochester, Gov. John Carney and many others who spoke mentioned virtually all religions except Sikhism. It was only U.S. Senator Chris Coons who reminded the crowd of the shooting at the gurdwara in Wisconsin.

I’m sure the officials’ omission was not intentional; we are a tiny demographic in America compared to other religions, but passing Sikh Awareness Month resolutions (April) in the Delaware legislature that I started in 2017 must go on for many more years, I resolved.

When Sunmeet and I walked to the parking lot that Saturday after the Shabbat service, a woman stopped her car near us. She was in tears. She blew kisses at us while saying, “Thank you for coming!” Sunmeet later told me that two of her loved ones were among the eleven victims in Pittsburgh.

A reminder of how far we all need to go to expand our understanding came when a couple of Sikhs questioned me for going to the Shabbat service, just as many Sikhs and others ask me every year why I host Iftar dinner during Ramadan. Others question my celebrating Christmas, Diwali, Lohri, Holi, Passover and other festivals.

“Why not?” I reply.

“You are a Sikh.”

“Precisely. I only feel Sikh when I am doing this because my Nanak’s blessing of ‘Sarbat Da Bhala’ hugs me warmly and blissfully only during such moments.”

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.delawareonline.com on Nov 9, 2018.

by blogadmin | Nov 8, 2018 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Year 2018

IT was the Saturday after. The first Shabbat service in the aftermath of the Pittsburgh tragedy was about to begin. A friend and I entered the local synagogue in Newark, Delaware. Rabbi Jacob Lieberman, a short, handsome man, stepped off the dais to welcome us. After returning to the lectern, his hands rose repeatedly to his face. Then he left. I noticed other congregants looking at us with kindness. He reentered after a couple of minutes and looked at us all. He was still crying.

Growing up in Punjab and working in India, the US to me, and like others, was a land of opportunities. No wonder, then, that an Army havaldar’s son could think of starting a software company immediately after landing there in 1999.

It has been especially painful to witness the hatred expressed by a tiny, but lethal, group of individuals in this country. Six years ago, it struck a gurdwara in Oak Creek. Recently, a synagogue in Pittsburgh. In between, a black church in Charleston. All three tragedies were perpetrated by lone white supremacists; all three at places of God; all three at an interval of three years. And then, there were additional tragedies in schools across the country, the concert in Las Vegas, the nightclub in Florida….

My friend and I were at Temple Beth El to express our solidarity. The sinking feeling I had after hearing about the Oak Creek shooting is still fresh with me. I was in Bengaluru that day, visiting my India operations with my family. My wife and I were worried about our son. He was then, and even today, the lone Sikh boy with long hair to ever attend his private school in its century-old history.

He has private violin lessons in a neighbourhood we know from the many Passovers we have enjoyed there. That day, I dropped him and went to the gym, where I learned of the Pittsburgh shooting. It triggered that familiar sinking feeling. I thought of my Jewish friends and their pain. The next day I joined hundreds gathered at a vigil in Newark. Addressing the gathering, including representatives of many faiths, Rabbi Lieberman said: ‘For our grief, this is an opportunity to mourn. For our outrage, it’s a time to cry out. For our fear, an opportunity to pray and to invite courage, and for our vulnerability, it’s a time to stand with others and to discover that we are not really alone.’

Later, a couple of Sikhs questioned me for going to the Shabbat service, just as many Sikhs and others ask me every year why I host Iftar dinner during Ramadan. Yet some others question my celebrating Christmas, Diwali, Lohri, Holi, Passover and other festivals.

‘Why not?’ I ask.

‘You are a Sikh.’ I am told.

‘Precisely. I only feel like a Sikh when I am doing this, because my Nanak’s blessing of sarbat da bhala hugs me warmly and blissfully only during such moments.’

– – – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.tribuneindia.com on Nov 9, 2018.

The woman who came to greet us at the table was the Adjutant General, the official host of the event.

The woman who came to greet us at the table was the Adjutant General, the official host of the event.

Recent Comments