by blogadmin | Sep 6, 2019 | Blog Post, Media Publishing's

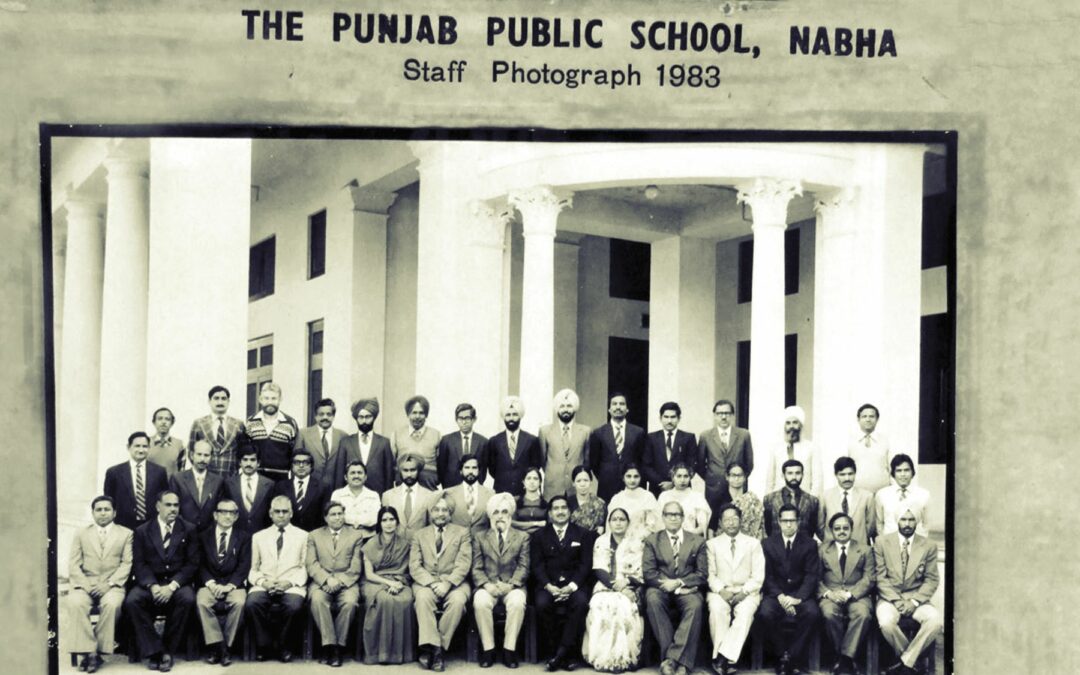

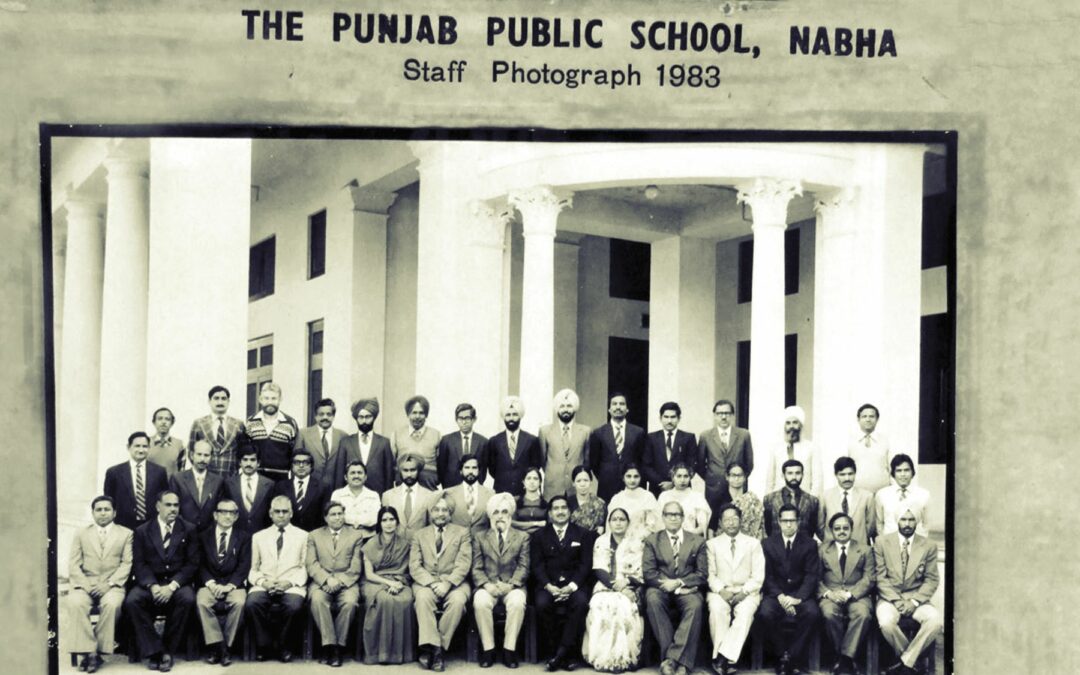

The Punjab Public School (PPS) in Nabha, is a great institution for reasons beyond its enviable infrastructure and stellar alumni such as Indian Army General Bikram Singh, or Hero MotoCorp Managing Director Pawan Munjal, or Wharton professor Jagmohan Singh Raju.

I was a student here for five years, beginning in August 1980. Most of the school’s success must be credited to its teachers, including founding headmaster JK Kate. One such teacher who must be given his due is KMP Menon; he taught economics.

Beas House picture (Mr Menon, with senior Beas House as its housemaster; sitting in the center, in this 1986 picture).

Several of Mr Menon’s students remember the way in which he reached out to them in times of desperation. They always reiterate how Mr Menon offered his help with love and grace. Even in the classroom, his approach to teaching economics was unique. I can vouch for this even though he never taught me. I had only experienced him when he came as a substitute teacher to my class.

I was in class 9. “How many of you know that Nizam of Hyderabad was the world’s richest man in his time?” Mr Menon had asked the class.

What he went on to narrate has never left me since that day in 1984. “Here is one of the ways in which he became the wealthiest: The Nizam was a smoker. He loved smoking expensive cigars. However, his frugality didn’t allow him to spend on them. Can anyone guess how he still enjoyed the most expensive cigars without spending a paisa on them?”

The clueless class looked raptly at his dark and calm face who wore a thick mustache, with curly hair nestled atop his head.

“He smoked the remainders his guests left in the ashtrays!”

I retold the story to a few visitors in Bangalore on 17 June 2015, as I sat by the bed of an unwell Mr Menon. My audience included my PPS companions, Naveel “murda” Singla and Deepak “thakur” Singh, in the room of the teacher’s younger daughter Mini’s house. Mr Menon squeezed my right hand after I finished: “You still remember that,” he said in a whisper, as tears streamed down his face.

As we were leaving, Mrs Menon stopped us and gave us a message from her ailing husband: “Waheguru Ji Ka Khalsa Waheguru Ji Ki Fateh!” This time, I couldn’t hold back the tears.

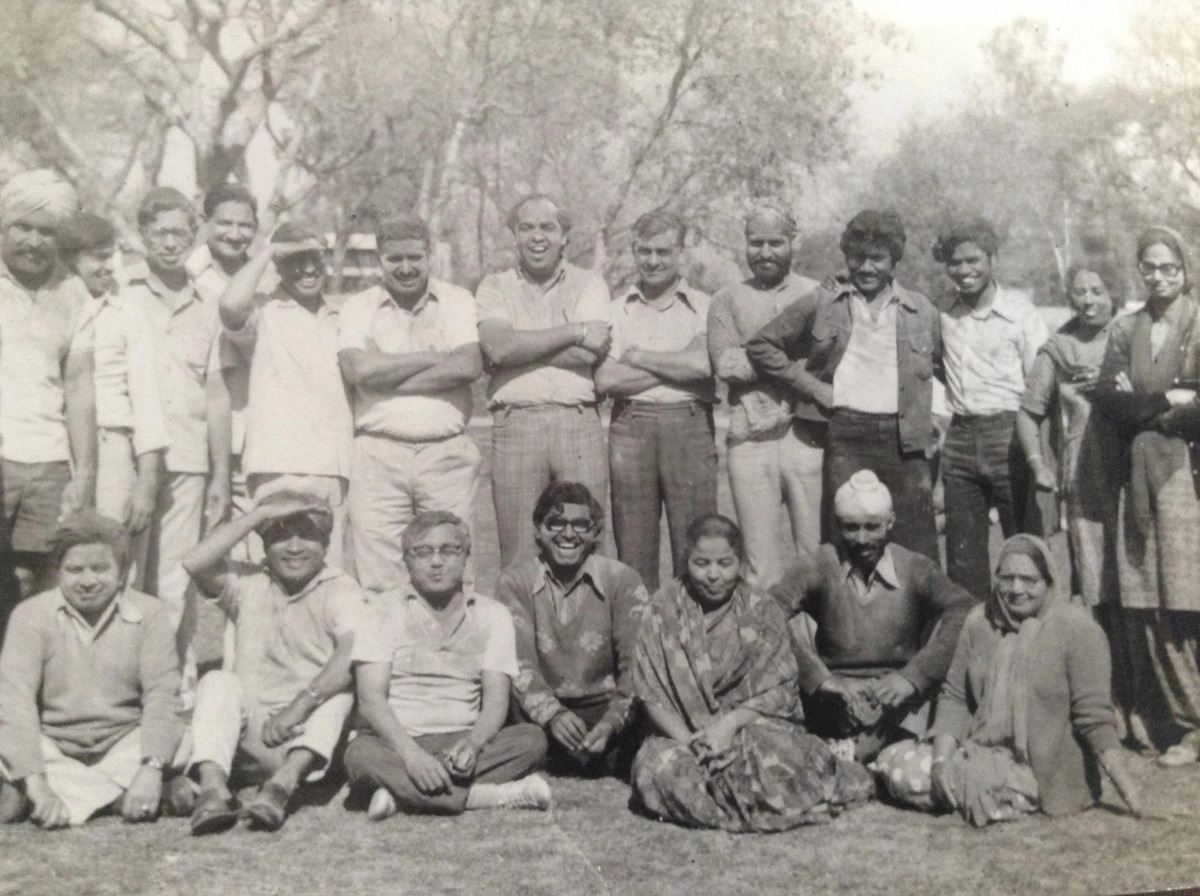

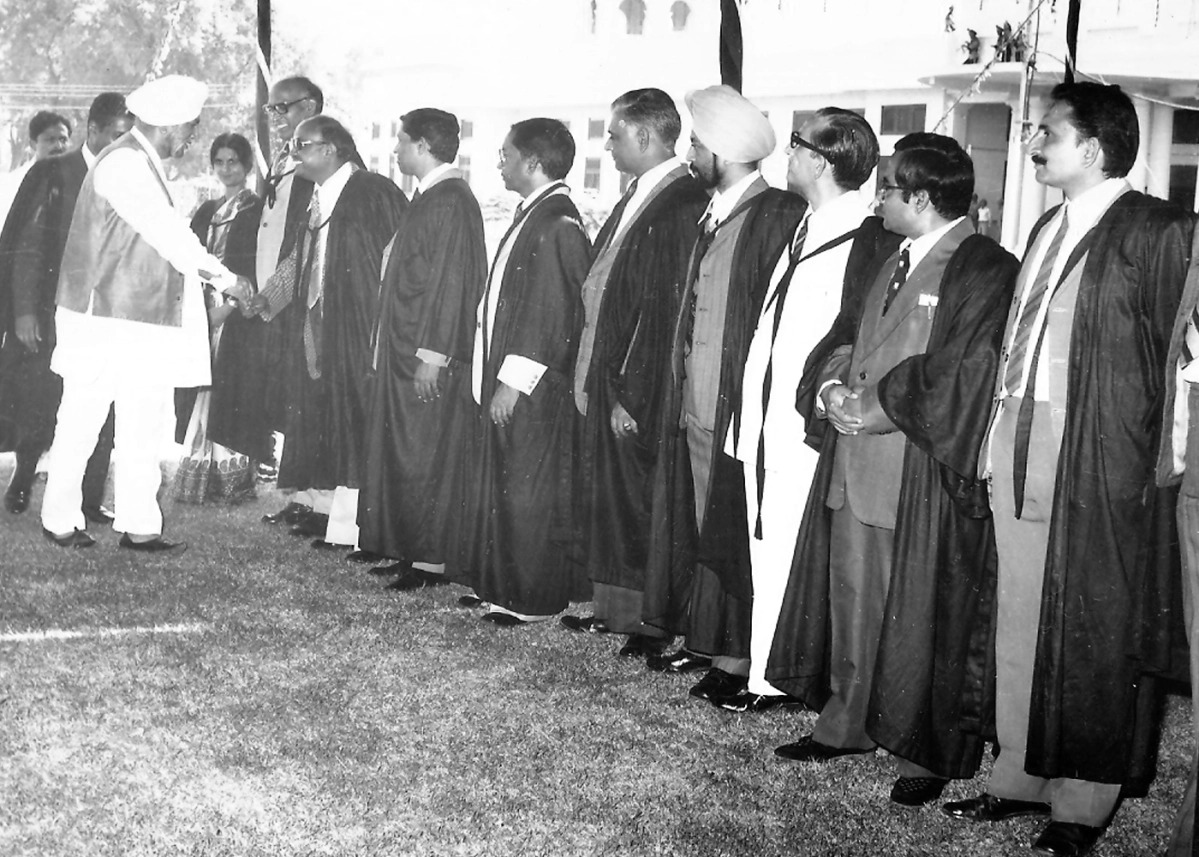

The school Headmaster, Mr. Manjitinder Singh Bedi, an old Nabhaite himself, is introducing the Founders’ Day chief guest to Mr. Ram Singh.

Mr Menon, the “Kindest Father”

Until then I had not understood how seriously ill he was. The following evening, as I had just started to sip my whiskey, the phone rang. It was Mini. Her father, Mr Menon, had passed away a few hours ago. I was in shock.

Mini also commented that after our visit the previous day, “Mom said your visit had brought a divine calm and joy on his face she had not seen in a long-time.” Both his daughters, Mini and Mickie, are still not “in a space to even have a photo of him in the house.”

Mr. Menon with his wife and two daughters visiting Golden Temple in 2017.

Said Mini of her father: “…kindest, most intelligent…the words dislike or hate never existed for him…had the most amazing Wodehousean sense of humor…I changed forever the day my dad left me. He wouldn’t have liked it at all. But that (is) the downside of having the perfect person as your father…”

How We Earned Our Nicknames

Another teacher in this legendary league was Mr Ram Singh.

Though I can’t say how many inches over four feet he was, he towered tall, and not only for those he taught mathematics to. His “kakaji” shouts echoed through the senior Jumna House for which he was housemaster, even in the winters — his well-known ‘enemy’.

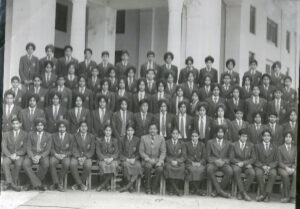

Mr. Ram Singh sitting third from left. (This picture was taken during the P.P.S. staff colony Holi celebrations in the late 1970s)

All of us in the school, especially the overwhelming majority who were boarders, were soon given nicknames by our peers, upon joining the junior school in classes fifth or sixth. My friend Rajesh “panditji” Sharma, who lives in Brampton, Canada now, was gifted his ‘middle name’ by Mr Ram Singh.

“Since I joined the school in eighth along with our Appu brothers, Rahul and Ashish, Mr Ram Singh asked me my name in the math class. When I told him, he went, “Oh, so you are panditji,” and that was that. Hardly anyone knew my real name, and that stays true till date. “A few of my neighbors here call me that because they have overheard my wife using it at times,” Panditji told me over a phone call on 4 July.

During Founder’s Day celebrations, Senior Master, Mr. Y. P. Johri, introduces the chief guest. Mr. Ram Singh is second from right, clasping his hands together over his belly.

Mr Ram Singh: A Stickler For Honesty & Integrity

I was home enjoying the American Independence Day holiday that Thursday. When I checked our ICSE ’85 WhatsApp group, I saw that Panditji had posted, informing us of Mr Ram Singh’s passing,

“Here goes another pillar,” I mumbled, and heaved a deep sigh.

Though Mr Ram Singh retired ages ago, he still lived in Nabha in a rented house with his wife. His only child, Pappu (Abhijeet Singh), lives in Sydney, Australia, with his wife.

Mr. Ram Singh in the middle in black glasses, with his wife and three former P.P.S. colleagues and their families. An early 2013 picture.

Shivraj Singh “Binnu” Brar, presently security chief of the State Bank of Patiala, after his retirement from the army, also has stories about Mr Ram Singh, who was his Jumna House housemaster.

“It was raining one day when Mr Ram Singh came into the house for a random tour when there was almost nobody in the house. He closed his umbrella and left it standing top-down against the wall of the entrance. We put it high up somewhere. When leaving, he could see it but couldn’t reach it.”

Binnu was good at many things, but academics was not one of those.

“Mr Menon was too good. Once I was trying to cheat in an exam and he was on duty in the exam hall. He came and gave me the book itself. When that didn’t end my struggles, he helped me find answers. With Mr Ram Singh it was slightly different. Once I copied Sukhwinder Singh “Sukhi” Grewal’s answers during our mathematics exam. When we got our papers back, Sukhi got 90, and I, only 45,” said Binnu, who had, at the time, indignantly gone to Mr Ram Singh with his grievance.

“If you can, right now, do even one of them correctly, I will give you 100,” Mr Ram Singh shot back.

Mr. Singh with his wife, son, daughter-in-law, son, and grand daughter in this December 2017 picture

How Two ‘Outsiders’ Stayed Back to Teach in Turbulent Punjab

“Mr Ram Singh had a special place in his heart and mind for farmers’ children. He went out of his way to help them and cajole them into doing something. I was part of the school band. Rumor has it that you had to at least fail in three subjects to qualify in the school band,” Binnu said. “Mr Ram Singh would tell some of us from the villages, ‘at least go join the school band.’”

While Mr Menon was from Ottapalam in Kerala, Mr Ram Singh hailed from Allahabad – in fact, Amitabh Bachchan’s dad taught him English when he was in college at Allahabad University. Their roots help explain why these two teachers are so revered. Punjab and the Punjabis were hapless victims of the senseless violence in the 1980s. These two “outsiders” stayed on to take care of and support us even when many Punjabis left in search of peace and security.

How can a school or its students ever repay such luminaries?

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.thequint.com on September 04, 2019.

by blogadmin | Aug 15, 2019 | 88to92 Engineering Batch, Blog Post, India, Media Publishing's, Year 2019

An event that took place in 1989 remains etched in my memory. It isn’t the first liver transplant or Sachin Tendulkar’s international debut. No, it’s also not about the fall of the Berlin Wall.

It is about an evening during my computer science undergrad second year at the BN College of Engineering, Pusad, and the college’s then Principal BM Thakare — popularly known as ‘Takla’ among the students.

Rain had engulfed the town and lightning was ripping apart the skies, when Gurminder, Chauhan, and I finally left the Mungsaji Bar — past its closing time. We walked towards the parked cycle-rickshaws outside and enquired: “Eh bhau, engineering college hostel?”

We broke into riotous laughter along the way in the rickshaw, while imitating Nana Patekar’s dialogues from Parinda — a film we had watched earlier that evening. Upon our insistence, bhau removed the rickshaw’s hood from over our heads.

The Terror That Was Principal Thakare

I don’t remember why and when we shifted gears and started to sing. But I remember us loudly singing Shalimaar’s song Hum Bewafa, when we approached the house of Principal Thakare, unaware of our surroundings until my more-academically inclined companions noticed it when the house came into sight, and panicked. The house stood alone, away from the road, between the bar and the hostels.

Their panic only made my Jinga Lala Hur Hur howling louder. Just then two long bursts of lightning illuminated a car backing out of the house. Seeing that even I panicked.

Our worst fears came true. The car screeched to a halt before the rickshaw and the principal jumped out of it. We almost stopped breathing and reluctantly got off the rickshaw, scared out of our wits.

“What’s wrong with you hooligans? Why are you all braying like donkeys in the middle of the night?” This wasn’t the thunder from the sky. We exchanged looks amongst ourselves with furrowed brows.

“We? No, no, sir…we…we were just discussing if Gurminder and Chauhan will get a scholarship for jointly topping the first year,” I said.

“Who was making a lot of noise on the road then?”

“Couple of other rickshaws go…” Gurminder fumbled with words.

“Four college boys… on a bike, sir,” Chauhan said, pointing towards the hostels.

“Many seniors just went past us, sir,” I chimed in. We started to breathe again when Principal Thakare got back into his car. That’s the kind of terror Mr Thakare elicited from both students and staff.

A Lesson In Humility From Principal Thakare

He was the principal of the college from its inception in 1983 until 1996, and then stayed on as director for the next ten years, before moving to Nagpur for good. The rickshaw caper was not the only incident that showed Mr Thakare’s authority and persona.

Sandeep Chahal from Rohtak had just joined the college’s civil engineering course in 1990. A few months later, he and his friends were caught by the hostel warden drinking, dancing and peeing on the hostel roof. They were all summoned to Mr Thakare’s house the next day. It was a Sunday.

“He scolded us, shouted at us, and asked, ‘Should I rusticate you all or give you a chance?”

Sandeep quotes Mr Thakare often when he addresses the student community of the college he runs in his hometown now.

“Principal Thakare kept pacing back and forth in the verandah of his house like a pendulum while we stood below looking bloodless. No one was breathing. After a gap of every two oscillations, he would reach the switchboard and press a button, first on and then off. I stood there reminiscing Sholay’s Gabbar Singh, but singing Maar Diya Jaye Ki Chhod Diya Jaye Bol Tere Saath Kya Slook Kiya Jaye in my head,” Sandeep recalls.

One of Sandeep’s accomplices was Anil Rathee. He was a rebel, in love with trouble. His experience with Mr Thakare was a bit different.

“When I joined the college back after one-year rustication, I was determined to prove Mr Thakare’s saying, ‘you will never pass,’ wrong,” said Rathee. “After graduation I went to meet him.”

“Do you know why I had rusticated you?” Mr Thakare asked him.

“Because of what I did.”

“No, to teach you how important it is to be humble. Life humbles everyone.”

Principal Thakare, The Disciplinarian

Sometimes Mr Thakare’s lessons were a bit more forceful, as Sanjay Grover found out. Sanjay was a year junior to me in the college. He was academically better than his circle of friends. Initially, he used to help them cheat. One day, while walking towards the canteen, he made an about-turn upon seeing the principal heading in his direction.

“Mr Grover,” Mr Thakare called out.

“Yes sir,” Sanjay meekly answered.

“Change your friends and habits,” he said calmly, “and stop doing what you are doing.”

“I don’t understand, sir,” Sanjay replied, applying the ignorance is bliss theorem to the problem at hand.

“Let me be clear, Mr Grover. You are on oxygen and guess who controls the supply? Before Sanjay could answer, Mr Thakare said, “ME!”

How BM Thakare Built An Institution & A Community

As former students recalled their “teaching moments” with Mr Thakare, the faculty remember his commitment to the college. Mr KR Atal taught us mathematics in the first two years. He described how the college evolved from just a badminton hall to what it is today because of Mr Thakare’s vision and work ethic.

“Even in only the badminton hall days, the college’s functioning was smooth,” he said. Later, all classes, labs, library and offices were moved to the current workshop building once it stood up. Mr Thakare was the first one, every day, to reach the college on his scooter. He would greet and welcome students and staff when they entered. All this when he was often the last one to leave.”

His dedication inspired countless former students, even long after graduating, to become Principal Thakare’s ardent followers.

Thousands in India and hundreds spread across the globe felt obliged to visit him in Nagpur whenever possible, and took pride in posting their pictures with him on social media.

Principal Thakare was overwhelmed by the respect and gratitude, as the tears in his eyes often revealed.

The Devolution Of BM Thakare’s Grand Institution

His ability to build an institution extended to the community. Besides overseeing the affairs of the institution and teaching final year civil engineering students, I cannot understand how he still managed to regularly appear everywhere: from the hostels, the mess halls and college canteen, to private houses rented outside by the students.

The college was booming in those years and he loved steering its growth. Each year saw new additions. From hostels to classes to tennis courts and an administrative block, library, and auditorium — all grew under his direction and supervision.

The college of the time was a multicultural, multilingual and multicoloured garden in full bloom.

No wonder the remote and impoverished Pusad taluka was benefiting from it in more ways than one.

Responding to the growing demand, many new shops, lodges, restaurants, and bars opened up in Pusad. A beautiful garden park also was added between sootgirni and the college. I was still in the college when the local MLA, Sudhakar Rao Naik, became the state’s chief minister in 1991.

I visited the college briefly in 2013 and found that everything had changed. Though the whole college had gathered at the state-of-the-art auditorium to greet me, barely half the room’s capacity was filled. I couldn’t oblige the students when they asked me to speak only in Marathi — not Hindi or English.

Principal Thakare’s Demise: ‘Losing A Mentor, Teacher… My Pappa Ji’

The college looked like India’s concrete jungle metropolis, sans traffic. The empty hostels and near-empty classrooms were sulking—not so silently. Contrast it with my time, when three of us were packed in each hostel room designed for only one.

Pusad, too, had nothing uplifting to offer. A lot of bars, restaurants and other outlets I frequented in my time had died. Sootgirni had closed. The Naik family’s influence, the town’s crowning glory, was rapidly evaporating.

Last year, in Vancouver, I organised an alumni reunion of college students. Someone whispered that the college would soon close because it was struggling with admissions.

I am sure principal BM Thakare knew the state of his “child” only too well. How could he stay to sift through its ashes?

He passed away in the wee hours of 14 July this year.

Thousands of his former students’ messages like this one from the current principal, Avinash M Wankhade, on Facebook, reflect what they felt: “Today I am speechless…feeling alone…I lost my best teacher…I lost my mentor…I lost my PAPPAJI.”

by blogadmin | Aug 12, 2019 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Year 2019

“Everyone parks their powers and positions outside the front door. You walk in here as a person — not a lawyer, judge, doctor, editor, mayor or senator.”

Gary Carroll’s proud tone underlined what he said.

Gary was my show-and-tell guide of the Monday Club earlier this month. A plaque on one of the club’s walls listed him as a platinum contributor to the club’s 2018-19 remodeling project. A similar plaque bore names of those who have been members of the club for 30 years.

Also adorning the club’s walls were a set of neatly framed pictures of the distinguished club members, among them: Dr. Woodrow Wilson, Delaware’s first black dentist; Herman Holloway Sr., Delaware’s first black senator; Norman Oliver, former Wilmington city councilman and business leader, with President Barack Obama.

Gary is proud of the club and his association with it, something I learned two years ago when he first told me about it.

The club came to life in a tavern on Wilmington’s Front Street (now MLK Blvd.), across from the train station. Its founders were seven “colored” men.

When? No one knows precisely, except that it was in 1876 and it had to be a Monday.

The club got its name because Monday was the day off for “service” workers such as chauffeurs, cooks, butlers, waiters, janitors, coachmen and house servants, jobs that many black workers performed in those days.

“The Monday Club” was incorporated on Nov. 4, 1893, and received a permanent charter in June 1913. That makes it the oldest African-American organization in continuous service not only in Delaware, but in the nation, according to Vincent Robinson, popular as “the historian” in the club, where nicknames are a tradition.

Baltimore’s Arch Social Club earlier claimed the “most antique” tag until Vincent called them one day.

“Upon seeing the web page, I contacted the club and informed them of the Monday Club, Inc., and that their date of incorporation was 19 years later,” he said.

The Arch Social Club reacted to the news gracefully, Vincent said. A few weeks later it sent the Delaware club an invitation to visit, and eight members of The Monday Club drove to Baltimore for the fellowship opportunity.

Once the club had a legal birth certificate, it needed a cradle. On Oct. 15, 1896, the group bought a lot on French Street. Then, in the same year, on the same street, the club bought the building at 917 followed by properties at 915 and 913.

Those locations were purchased by MBNA when the club moved to its current home at 4020 New Castle Ave. in New Castle.

For almost a century, the club remained a male den. Until 1989, no women were allowed to enter.

“Founders wanted a place where they could drink in peace—meaning without the presence of women,” The News Journal reported in 1996.

At one time, a member was fined $5 if his wife or girlfriend even rang the front doorbell. In protest, the ladies started to form their club. The sassy name they came up with —The Tuesday Club — was biting. That club disappeared after the men’s club changed its rules to allow women on the premises.

Although women today remain frequent attendees, and even employees, there still are no females among the Monday Club’s 125 members.

Julius “Jay” Jackson is a retired attorney, an astute photographer and a writer. His father was one-time president of the Monday Club.

Although he is not a member, he says, “I have tried to emulate the examples of service that were shown to me by my father and other members of the club. I learned from an early age that I have an obligation to serve the community and make life better for others. I have tried to do this in my professional and personal life.”

He continued: “I would say the club started as a necessity…survival for black males. That brought certain closeness, looking out for each other. Folks took care of each other in the Monday Club, they looked and found jobs for each other, got various blacks elected to the Senate, the House and the city council. The Monday Club members were role models for young African heritage males growing up in Wilmington.”

That support and success could bring change.

“Negro Rules the City,” screamed the headline in The Evening Journal in 1896 when club member Thomas E Postles successfully outmaneuvered Democrats and Republicans to become the head of the Wilmington City Council.

Jay directly benefited from the club’s attention as well by helping him get to college and supporting him and his mother when his father died.

“They gave me a foundation to believe in myself, that I can be successful,” he said. His gratitude to the club was unmistakable.

Many others have benefited as well. In 1893, the Monday Club began an annual ball tradition.

At the ball, the Monday Club Man of the Year is named. This honor is bestowed on a member who has made the greatest contribution to the club and/or community.

My wife and I attended this year’s 125th annual ball at the Chase Center on June 22 where five $1,500 scholarships were awarded. Each year these scholarships are given to Delaware’s senior high school applicants of African-American, Hispanic or Native-American descent.

“Over the last eight years, the Monday Club has awarded over $67,000 in academic scholarships to deserving Delaware high school students to attend a four-year college or university,” the club reports.

The ball raises funds for other causes as well including the Wilmington Little League, Sharpshooters Elite Basketball, Adopt-A-Family and Thanksgiving Turkey Drive.

To extend the Monday Club’s proud history, it needs to stay relevant in the contemporary world and useful to the next generations, according to Vincent Robinson.

“We need to adapt, innovate and recruit female and younger members,” he said.

For more information about the Monday Club, visit its website at themondayclub.org.

– – – – –

This column was published online by the News Journal/Delawareonline.com on Monday, August 12, and printed in its Monday, August 12th edition.

Website Link: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/opinion/contributors/2019/08/12/opinion-once-refuge-black-men-now-beloved-community-club/1965620001/

Print Version:https://charanjeetsinghminhas.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/once_a_refge.jpg

by blogadmin | Jul 5, 2019 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Year 2019

“What do you think of doctors?” I have been asked.

“A heartless tribe of professionals experienced in focusing on your wealth while pretending to care for your health,” has been my reply.

But one of the physicians here in Delaware changed my mind.

I have observed him closely for years. He and his wife are both internists in Wilmington and practice under Trinity Medical Associates.

His name is Vinod Kripalu, MD, but everyone calls him Vinny. She is Chetana Kripalu, MD, and everyone calls her that.

Vinny could be mistaken for a famine victim with his frail frame. But his meager physique is not the result of poor nutrition, just a seemingly inexhaustible energy. An avid runner, last December he kept going for over 26 hours until the 100-mile mark finally stopped him.

The Kripalus’ devotion and dedication to helping and serving the needy, however, is unstoppable.

In 2006, Vinny organized his first visible philanthropic effort through a “Brick by Brick” fundraiser. The twelve thousand dollars it raised were used to build a school in Kenya. In 2008, he and Chetana provided their services on a medical mission to Jamaica.

He also established two nonprofit organizations he still serves — the Delaware Medical Relief Team (DMRT) and Premiere Charities Inc. (PCI).

The medical relief team was created in 2009 after an earthquake devastated Haiti.

“We were the first team to go within a few days of the earthquake. DMRT sent out seven teams after Haiti and five after the Nepal earthquake,” he told me.

Their service also helps those closer to home. Each Sunday, rain or shine, From Our Kitchen, a program of PCI, provides food to the homeless and needy at Front and Lombard in Wilmington. The organization feeds about 180 people in each service and has provided more than 80,000 meals since 2009.

PCI has raised more than half a million dollars over the years and contributed each cent to several relevant local and global causes such as the fund for families of deceased local firefighters, help for families affected by diseases such as breast cancer, and aid for victims of a Pakistan earthquake.

I was among those who attended PCI’s fundraiser gala in April at The Waterfall banquet hall in Claymont. I watched in amazement and admiration as Vinny’s father, 93-year-old father, Thirumalachar Kripalu, danced with his daughter-in-law, Chetana.

Curious about the Kripalus’ impulse to help, I reached out to Thirumalachar to trace his son’s roots.

“I had a very tough childhood,” said Kripalu, a retired Indian army brigadier. “We were extremely poor, had nothing. Existence was becoming tough. As a kid, I started begging to earn something and would give it to my mom. This habit of sharing with others became a satisfying habit.”

Kripalu continued: “I was a major posted in the UK when Vinny was born there in 1964. I cannot say whether I influenced him, but one thing is certain: Chetana has a lot to do with his giving. She wanted to serve the needy even more.”

In August of 2015, Chetana and her daughter, Meera, along with Meera’s friend, Hannah, and a nurse traveled to Nicaragua to establish a health clinic.

“Chetana was the only doctor and worked long hours daily at the clinic in Pantanal, one of the poorest barrios in Nicaragua,” according to Chuck Selvaggio, executive director of Neighbors to Nicaragua, a Wilmington nonprofit. Meanwhile, Meera and Hannah volunteered at a nearby school, working with and feeding the children.

“Both Chetana and Vinny have been very supportive of our work, contributing time, financial support (paying for many of the medications given out at the clinic), and, most of all, encouragement and inspiration by example in the great work they do and the wonderful people they are,” Selvaggio said “Their lives are nothing less than a great gift to our community and all the people they serve worldwide.”

It takes a long time, lots of fortitude and some luck to succeed in doing good. Not many doctors like Vinny and Chetana envision “state of complete wellbeing” for their patients by “nurturing their body, mind, and spirit.”

It is fitting that their work reflects the meaning of their Indian names. In the case of Vinny and Chetana, their first names mean happiness (Vinod) and consciousness (Chetana). Kripalu means indulgent.

Maybe that’s why they are happily and consciously indulgent!

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.delawareonline.com on July 03, 2019.

by blogadmin | May 29, 2019 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Year 2019

You are not a Muslim. You have no Muslim friends. And you haven’t seen, read or heard anything positive about Muslims — ever. You never came across anything nonviolent and not disgusting about them.

Me neither!

No matter where I went, Muslims had always been in the news for the wrong reasons.

In India, the UK and even during my last 20 years here in the U.S., I have seen the anger and animosity against Islam and the Muslim communities only grow stronger and louder over the years. President Trump successfully rode it, among other things, to the White House.

I was home drinking tea in Dover on 9/11. In 2009, my wife and I, along with our two children, stayed at The Taj Palace Hotel in Mumbai, India where, only a year earlier a terrorist attack had killed 166 people.

Perpetrators in both cases were Muslims.

Internationally, we constantly hear about the barbaric and inhuman acts of Muslim terrorist groups like ISIS, the Taliban, Al Qaeda, Boko Haram, the Khorasan group, the Haqqani network and their offshoots.

An interfaith coalition distributes food to the homeless at Front and Lombard Street in Wilmington

Reaction to these groups and incidents often are quick and emotional. In Delaware, two Republican state senators

walked out of the Senate during a Muslim prayer in April 2017. The reason, one of them said, was that women and minorities are not treated fairly and respectfully by Muslims.

With no or negligible interaction with Muslims, does the negative barrage make us believe that all followers of Islam are constantly conspiring to commit evil? To explore that question, I launched a soul-sponsored expedition to discover the truth.

I asked Islamic Society of Delaware’s (ISD) interfaith chair Irfan Patel for his reaction to the senator’s allegation. “His actions show lack of understanding of our faith,” he said. “Islam teaches equal rights to men and women. In fact, laws of inheritance are a prime example of how women’s rights are respected in Islam. To give some context, women were not given electoral rights in many western societies until recently.”

I am a Sikh. Delaware’s second gurdwara (Sikh temple) opened in the summer of 2015 in Middletown. Weeks after, I organized an interfaith peace prayer there in August to mark the third anniversary of the Oak Creek, Wisconsin gurdwara killings.

We had decided on one speaker from one house of worship for the event. But, a couple of days before the meeting, I received a call from a stranger who turned out to be a professor at the University of Delaware.

He dispelled my “only one mosque” assumption. “There isn’t only one, not even two, but seven mosques in New Castle County,” he enlightened me. And Patel confirmed there are in fact 12 mosques in Delaware serving the state’s more than 10,000 Muslims.

Delaware’s Muslim community is as diverse as our nation. Its constituents are men and women of African, Middle Eastern, South Asian, Far Eastern and even European origins. They represent a range of human endeavor: business, academia, engineering, construction, health care, medicine, computing, art, music, writing and poetry.

Similarly, their food, dress, interests, opinions and friendships are varied.

I meet many members of the Muslim community at interfaith events throughout Delaware. They are eager and reliable participants in the Interfaith Peace Walk I organize every April on Newark’s Main Street. Led by Vaqar Sharief and his wife Uzma Vaqar, they join in the distribution of food to the homeless and needy each month at Front and Lombard in Wilmington.

Naveed Baqir of Delaware Council on Muslim and Global Affairs was in the Senate to read the Muslim prayer when the senators walked out.

“I met with both of them afterward,” he said. “Since then, they have supported us. Recently they supported a concurrent resolution (HCR 46) on the Ramadan month,” Baqir said.

It was similarly heartening to read the New York Times story, “Muslim groups raise thousands for Pittsburgh synagogue shooting victims.”

In recent weeks, many Muslim organizations have been hosting Iftar dinners to celebrate Ramadan. These events have wide participation from the community, including non-Muslims.

There is an undesirable vacuum between Muslims and non-Muslims everywhere that allows for misunderstandings and stereotypes which are often exploited by those with their own agendas and uninformed views. A continuing effort from Muslims and non-Muslims alike needs to be made and sustained to bridge this gap.

In the meantime I salute all of those, in Delaware and beyond, who are already working to do so.

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.delawareonline.com on May 29, 2019.

by blogadmin | May 13, 2019 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Sikhism, Year 2019

Years ago, I was at a college classmate’s house in my hometown, Patiala. His retired colonel neighbor asked me, where in the United States I lived. “Delaware,” I replied.

“Umm…Where?”

I repeated, slowly, “Delaware.”

The colonel narrowed his eyes, picked up his large tumbler of some strong drink, (rum, probably), gulped it in one go, and said, “Delaware…huh? What kind? Software or hardware?”

Could this ignorance, coupled with bigotry, have led to the killing of three Sikh women and a Sikh man at an apartment complex in Ohio’s Cincinnati city, on 30 April? While External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj had said that this was “not a hate crime”, questions continue to linger amid investigation into the case.

Is it possible that the Sikh family was more vulnerable (in the eyes of the perpetrators) because they were Sikhs / Asians?

Sikh Diaspora in Delaware & Cultural Diversity

Almost all the South Asians living in Delaware are first generation immigrants. As long as they could eat their rice or rotis at home, their cultural and religious aspirations rarely superseded family and economic priorities. Therefore, I was amazed to see a huge (and diverse) turnout at Lalkar 2019 , a national collegiate bhangra and fusion dance competition. From the 62 university teams that had applied, eight teams were selected to perform at the University of Delaware.

Significantly, the event’s success was a true tribute to the message of Guru Nanak in his 550th birth year—bringing people together in respect, peace and love.

On 19 March, the Delaware Sikh Awareness Coalition (DSAC) organised a luncheon in Dover, the capital of Delaware. It was before we went to the state Legislative Hall, where the Senate and the House were scheduled to pass a concurrent resolution, declaring April 2019 as ‘Delaware’s Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month’.

The participants at the luncheon were a diverse lot, and included men and women as young as 16 and as old as 86. Those originally from India included Gujaratis, Punjabis, Sindhis, Delhiwallahs, UP, Bihar, MP, and many from the southern part of India. Among the Americans there were people across Christian denominations, and one Jew.

Various community leaders, legislators and individuals of different castes, colour, abilities and professions were in the audience. Many of them even took the opportunity to experience wearing a Sikh turban.

‘Why a Real Tribute to Guru Nanak Should Be An Interfaith Celebration’

The topic of discussion at the luncheon was ‘Why a real tribute to Guru Nanak’s 550th should be an interfaith celebration’. Most had never even heard of Guru Nanak.

Starting from the “Na ko Hindu, Na Musalman” (No one is Hindu, no one is Muslim) proclamation after his communion with God in 1499, Guru Nanak used art (writing hymns in divine poetry) and music to take his message of Ek Onkar (all creation by one creator) to the world. Along with two companions, Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana – the latter playing the rubab – Guru Nanak used melody and music to spread his message.

His successors temporally and spiritually built on the foundations of peace and communal harmony that Guru Nanak had laid.

Among the 36 were Baba Sheikh Farid, Bhagat Namdev, Sant Kabir (the maximum contribution by a non-Guru author and the fifth largest among all authors), Bhagat Ravidas, Bhagat Kalshar, Bhagat Nalh.

The holy text also depicts the importance of dissent, and that too, respectful dissent. On page 1380 of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Guru Amar Das disagrees with Baba Farid ji after more than 250 years, and the divine dialogue is presented in a sublime way. In fact, Farid ji’s bani (hymn) is in the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, before which millions bow their heads every day. This also depicts the virtue of tolerance and regard for all, that Sikhism embodies.

What Guru Nanak Truly Wanted

At the end of the presentation, a slide show on Harmandir Sahib, whose foundation was laid by Sufi saint Mian Mir Sahib, was presented – to further illustrate the point of communal harmony and religious tolerance. Post-luncheon, we went to the Legislative Hall where Delaware Senator, Bryan Townsend, introduced the resolution in the Senate, and Representative Paul Baumbach introduced it in the House. It was unanimously passed in both the chambers. Governor John Carney signed an executive proclamation, declaring April 2019 as ‘Delaware Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month’.

This was the third year in a row that this feat was accomplished. But what made this edition stand out is the participation of diverse groups, across communities. This is what we believe, Guru Nanak really wanted.

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.thequint.com on May 13, 2019.

Recent Comments