Interfaith Peace Walk – 2022

About this Event

Just like the earlier years, we had started our annual Walk DE Talk from in front of the Old College Hall on East Main Street in Newark at 01:00 P.M. and ended it in the New Ark United Church of Christ, less than a mile away. Once there, everyone who attended was encouraged to share a message of love and peace—if he or she wishes to. Before leaving we all took group pictures, and wished our city, state, country and the entire universe all the best.

Different faiths share many core celebrations, and offer hope during troubled times: Opinion

Twenty-one years ago, when I came to America from India, I was amazed by its opportunities. Wasting no time, I started a software company that will celebrate its 22nd birthday next May. Doing business in the country was more straightforward, and accessibility to various institutions was much more comfortable than in India. However, when it came to how our president is elected, I still can’t say I have all the answers.

After a few years here, I realized that not everything between the two countries is different. Both are democracies, of course. More remarkable to me has been how America resembles India in look and spirit during their respective year-end holiday seasons. Homes, offices and markets in both countries are lit up during this period because of the different festivals and traditions each country celebrates.

For Halloween, Thanksgiving, Hannukah, Christmas and New Year’s Eve here during these weeks, India has Dussehra, Diwali, Bandi Chhor Diwas, Guru Nanak’s birth anniversary, Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Diwali is the greatest of them and celebrated nationally in October or November as per the dictates of the lunar calendar. It is celebrated on the same scale as Christmas in America and other Western countries.

Diwali is also called the “festival of lights,” and fireworks are an integral part of the celebration. Thanks to last year’s efforts and the initiative of Jay Muthukamatchi, it became possible for the first time in Delaware to buy and sell fireworks 30 days before every Diwali.

Halloween reminds me of Lohri (a bonfire celebration), which falls in the middle of January. Looking at boys and girls in the neighborhood going from door to door asking, “Trick or treat?” I recall my Lohri days as a young boy going with a group of other boys to various houses on my home street and adjoining lanes asking for “Lohri!”

The grand Annakut celebration at the BAPS Swaminarayan Mandir (Temple) in New Castle. During the celebration, there is an offering of different kinds of goods to God, accompanied by prayer. Annakut is part of the five day Diwali, or “Festival of Lights,” which coincides with the Hindu New Year and is celebrated around the world by millions of Hindus, Sikhs and Jains.

Neighborhood folks gave us cooked groundnuts and traditional Lohri sweets made from jaggery. It was incumbent upon those neighborhood houses to be extra generous in giving where a son’s wedding had recently happened, or they had been blessed with a male child. The gender bias has since largely passed, but unfortunately some of it still lingers on.

I am a Sikh. In Thanksgiving, I see the personification of Sarbat Da Bhala (prosperity, well-being, and glory of the whole universe) spirit. Every Sikh prayer, no matter what occasion, day, time, and place, ends with these three words: Sarbat Da Bhala.

I, too, said these words with everyone else because I had seen my parents, siblings, relatives and other Sikhs do the same. But I understood its essence only after arriving here in America and experiencing Thanksgiving and learning its background. To me, native Indians had enacted and personified the Sarbat Da Bhala’s underlying meaning in the Sikh prayer.

This year, while I am happy to see lights on neighbors’ houses and front yards, I can also see apprehension in many of their faces about what this election and the days and weeks following it will bring. Maybe the lights are illuminating the darkness convulsing our hearts and minds ravaged by the soaring coronavirus numbers, historic unemployment, increasing pain and suffering of the poor and vulnerable, and divisions like never before among this country’s various communities.

Regardless of whether America retains Trump or sends our Delaware’s Joe Biden to the White House, I want and wish that there be a light for everyone in the embrace of hope and peace.

Delaware Air National Guard Adjutant General Carol Timmons (center left) speaks with Charanjeet Singh Minhas of the Delaware Sikh Awareness Coalition at a Thanksgiving prayer breakfast.

Fortunately, I know of many ordinary Delawareans doing extraordinary work toward that goal: veterans in the Interfaith Veterans Workshop group founded by Rev. Tom Davis; members in my writing group, Brandywine Writers Circle, founded and led by Joan Leof; and a host of others — pastors, imams, rabbis, Hindu and Sikh priests in Delaware — who are part of efforts to spread love and peace and defeat hatred and violence.

They are all — in their languages, in their traditions, in their own homes or their places of worship, in their own words and ways — praying for Sarbat Da Bhala.

Why Indians in America don’t support Blacks?

It was 1982. I was in my older cousin’s village in India’s Haryana state during my school’s summer holidays.

One morning, while my cousin was watering the paddy fields, which spread all around his tube-well — I saw him signaling a Dalit, or an “untouchable,” girl standing in the middle of the fields. She came over to us. Next, as if the two had been rehearsing this scene for a long time, both silently entered the bricked enclosure that sheltered the well.

“Keep looking…no one should come on this side…ten minutes,” he told me while folding the wooden planks of the room door shut.

I was old enough to know what happened in “ten minutes,” but did not understand the reasons behind the depraved sexual exploitation until much later. The fields, with or without crops, were — and still are in many Indian villages — the only open-air toilets in the places that lacked septic or sewage services. The tube-wells for most villagers were their single source of water and its tanks their most convenient destinations for washing laundry and large pots.

Landless lower castes, especially Dalits, submitted to the upper caste farmers’ exploitation in return for permission to use these facilities. How could they survive without the tube-well water and using the fields?

Just like that young city boy in the 1982 Indian village, I knew nothing about racism in America when I landed here twenty-one years ago. Even now, I struggle with the question, “What is your race?” asked on a form or an application. For Indians, it is easy to identify one’s caste simply because it is part of everyone’s name.

I had read that equality and liberty for all are guaranteed by the law, by the constitution, in America — it is securely lodged in the scripture of this great country. America’s economic and military muscle along with its international clout punished countries it accused of violating human rights. Upon arrival here, however, I learned that the same laws and the same constitution, when first written, failed to prevent one man from owning another. Black was the property of white. Legally. The owner could deed his or her possession to another like the title of a car.

Those who owned black people, stolen and kidnapped from Africa, included twelve American presidents, even the one who declared, “All men are created equal.”

In becoming a citizen of the U.S., I was shocked to learn all this but pushed it aside, ascribing it to a painful past not relevant in today’s America, one that lectures the whole world on human rights and values.

I learned differently on a Thursday in May of 2011, when two white guys and a girlfriend of one of them called me and my two friends “niggers” while we enjoyed a drink at a local establishment. For no reason.

When my friends went out to smoke, these three attacked them. The cops came and took us to the hospital because my friends needed stitches. The white judge gave the most violent of the trio only a six-month suspended sentence despite his long history of violence.

But I finally realized the ugly truth after watching and watching and watching George Floyd’s murder video. Derek Chauvin’s regally planted knee on George Floyd’s neck with his hand in the pocket was a proclamation that the white man is the undisputed master of the black man — a theatrical performance matching Ku Klux Klan (KKK) era public events. Bystanders’ pleas of mercy and “he can’t breathe” warnings gave the choker the high he needed to underscore his sense of superiority, impunity and entitlement.

Chauvin was aware he was being filmed and the whole world was watching him. In KKK tradition, the audience and the witnesses only made him more determined. He knew he had allies across America: The White House resident, Congress, judges, all Americans who elected Trump president for “taking America back” — as former KKK Grand Wizard, David Duke’s tweet proclaimed after Trump’s election and cabinet picks.

The only difference from the earlier KKK days was that Chauvin no longer needed to cover his face.

During their 200-year rule of India, the English abolished Sati — the self-immolation of the widow on the funeral pyre of her husband — quickly and resolutely but left caste cruelties intact.

They are natural allies, racism and casteism. They share so much in common.

Last year my wife was at her friend’s son’s birthday party in a local county park. The birthday boy’s older sibling had invited his black girlfriend and her family to the venue. When they arrived, the host family prayed for the earth to crack open and swallow them. The boys’ grandmother told my wife, “I don’t know what sins I did that my grandson, so intelligent and capable, is showing us this day…I don’t know where to hide my face.”

This colorism is a deeply ingrained issue in India and among Indians globally. In Punjab the saying goes, “Never trust a black Brahmin.” So, even though colorism existed in India before the Europeans’ arrival, the imperialists’ conquests and rule permanently embedded white superiority in Indian minds.

Most Indians in America are upper caste, not necessarily Brahmins, the top caste, but non-Dalits. (In 2003, only 1.5 percent of Indian immigrants in the United States were Dalits or members of lower castes, according to the Center for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania.) They view blacks as Dalits and adore whites as their role models and revere them more than their temple priests. They call whites “fair” no matter how unfair they are treated by them. They are their role models in life and look. That’s why Unilever’s “Fair and Lovely” whitening cream did $500 million of business in India in 2019.

Many South Asians have indiscriminately borrowed the white supremacist lexicon — blacks are inferior, dumb, dangerous, criminals, drug dealers and always on food stamps — and many refer to them as “habshi” — a derogatory Indian term for black people — in their interpersonal and communal conversations. An Urdu translation of “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” I am presently reading uses the term in reference to blacks.

I was surprised and disappointed to see the Indian-American community’s apathy toward George Floyd’s killing in my boarding school and engineering college WhatsApp groups and during discussions with friends and colleagues. I was shocked to hear and read, “What’s wrong with police killing a criminal?”

The millennia-long caste apartheid has made upper-caste Indians insensitive to discrimination. Years in college have given them the skills to earn but no reason to learn basic human values. Here in America, they have no Dalit friends. Research and surveys by Equality Labs show it categorically. No wonder that the immutable attitudes and approaches ensure ongoing discrimination.

Do they differ, racism and casteism?

Like most things western, racism was planted with objectivity in mind, namely its perceived economic benefits. In contrast, India’s casteism was primarily perpetuated because of subjective sociological distinctions. It is impossible for the colored to escape racism because skin color can’t be changed or hidden. However, in India today it is possible, though difficult, to sneak out of the caste cage. Those with education or skills can shed the crushing weight of the caste pyramid by moving to big cities where caste is not as visible. Some stop using their last names or change them to avoid caste identification.

Racism’s foundation is materialistic — economic exploitation. Cravings for status and power built the labyrinths of casteism. But their benefits are not mutually exclusive.

The Indians who don’t oppose white racism in support of the Black Lives Matter movement don’t realize that a white supremacist America will hurt and kill their children and grandchildren in the years ahead because they are perceived as blacks. Remember that white supremacy by its very name devalues and vilifies any non-white culture. The racially motivated attacks on Jews, Muslims and Sikhs in this country are proof of that. So why the growing Indian community in this country don’t realize this truth? At first, their numbers were too small to invite the attention of racists. Take the case of H1B visas. How drastically the reaction and reception changed over the last 20–25 years?

Democratic institutions and technological advancements haven’t loosened the grips of racism and casteism as many had hoped and wished. It is interesting to note that virtually all of the most successful Indian executives in America are of the Brahmin caste. If the New World’s most successful companies’ ownership remains white, its top management is becoming increasingly Indian upper caste. Is it an accident that Indira Nooyi (former Pepsico CEO), Satya Nadella (Microsoft CEO), Sunder Pichai (Google and Alphabet CEO), Shantanu Narayen (Adobe CEO), and Arvind Krishna (IBM CEO) — are all Brahmins. Ajay Banga, the Mastercard CEO, is no Dalit. The list is long and growing.

There are many who use data to argue how one race or caste is superior, more capable than others. Is the comparison fair? Haven’t the centuries of deprivation and subjugation played an undermining role in blacks’ lives? Don’t better facilities and opportunities have an enabling role? If not, why has no Indian citizen won a Nobel Prize in science or economics since the country’s independence in 1947? Only Indians who migrated to the U.S. and U.K have: Har Gobind Khorana (Medicine), Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (Physics), Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (Chemistry), Amartya Sen (Economics), and Abhijit Banerjee (Economics).

The only Pakistani, and the first Muslim — ironically, Pakistan didn’t consider him Muslim because he was Ahmadi — to get a Nobel Prize was Mohammed Abdus Salam, but only after his immigration to the U.K. Even the aforementioned Indian CEOs accomplished their stellar successes only after arriving in the U.S.

The solutions to inequality are — as the old saying goes — simple but not easy. Whether a Dalit in a squalid Indian village or a black child in an American slum, only equal education and opportunity over time can improve their lives collectively. As long as those benefits are restricted to the wealthy and powerful and to those of a certain skin color, caste, racism and discrimination will thrive. The availability of a long-term stimulating environment determines how living species grow. Until we commit to providing that nurturing opportunity to all people, regardless of color or caste, we have no right to judge them in ways that are unfair, unethical, and inhumane.

—————

This column was published online by the https://medium.com/ on July 30, 2020.

Opportunity to serve langar at New Ark United Church of Christ

“Vand chako” (share before you consume) is one of the values Guru Nanak Dev (founder of Sikhism or Sikhi) emphatically taught. Delaware Sikh Awareness Coalition (DSAC) is grateful to New Ark United Church of Christ for the opportunity today to serve them langar (complimentary communal meal) in commemoration of Guru Nanak’s 550th birth anniversary year. What a joyous experience it was!

Please let us know if we can do langar or another kind of service for your congregation or house of worship.

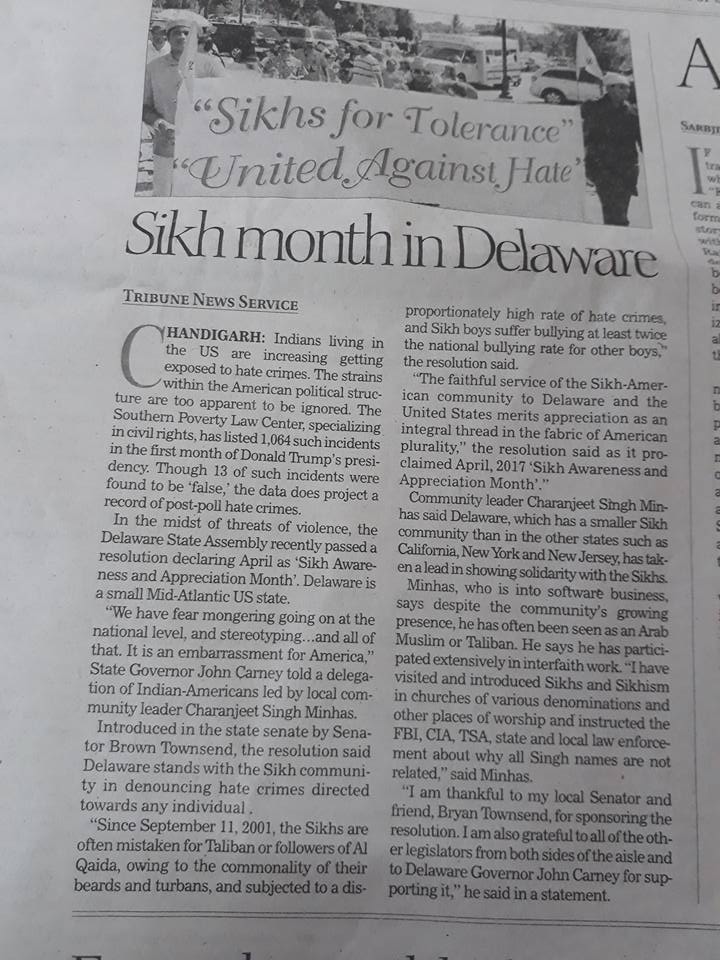

Sikh Awareness Month 2017

Delaware state proclaimed April 2017 as “Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month” in a joint resolution. Both the chambers passed SCR-3 unanimously. First the Senate and then the House.

Delaware state proclaimed April 2017 as “Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month” in a joint resolution. Both the chambers passed SCR-3 unanimously. First the Senate and then the House.

It became necessary to educate our fellow citizens that 99% of those you see with turbans are Sikhs, the followers of Sikhism, an independent, monotheistic faith. It is not a branch or blend of any other religion or religions. A path toward universal upliftment.

The highlight of the event, “Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month,” April 2017, proclamation by both chambers of Delaware legislature yesterday was when Jasmine Kaur Minhas got a standing ovation from Delaware’s Senate.

Major Minhas and Charanjeet Singh Minhas are holding the proclamation signed by New Castle county executive, Matt Meyer, for April 2017 to be “Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month” in the county. Matt is on the left of Major and Charanjeet.

Delaware’s Governor John Carney and state representative Paul Baumbach in meeting with Delaware Sikh Awareness Coalition in Dover.

Governor Carney is learning and appreciating the contribution the Sikh community and members of the coalition are making in the state’s progress. Seen in the picture are (clockwise): Gov. Carney, his two members of staff, Major Minhas, N eeraj Sharma, Brinder Singh Shergill, Charanjeet Singh Minhas, Anjali Gupta, Jasmine Kaur Minhas, Sunmeet Singh Sethi, state Representative Deborah Hudson, Harmeet Kaur Sethi, Lalit Jha, Vipin Kapoor, Harvinder Riar, Charanjit Singh, Riar Jr, state Representative Paul Baumbach.

Jasmine Kaur Minhas, standing in the middle, is happily showing the resolution. She is flanked by Governor John Carney and Representative Deborah Hudson. On the right end of the picture is also Representative Paul Baumbach, resolution’s sponsor in the House.

Charanjeet Singh Minhas proudly displaying the passed concurrent resolution. Present are(L-R): Row1 Kirit Singh Minhas, Harpreet Kaur Minhas, Harjit Kaur Minhas, Harmeet Kaur Sethi, Vipin Kapoor, Charanjit Singh, Suresh Choudhary; Row 2 Neeraj Sharma, state Senator Bryan Townsend (resolution architect), Harvinder Riar, Ajay Raman; Row 3 Riar Jr., Charanjeet Singh Minhas, state Representative Paul Baumbach, Sunmeet Singh Sethi; Row 4 Major Minhas, Surinderpal Sharma, Brinder Singh Shergill

Unity in Diversity: Different people, different colors, come together to make United States of Diversity.

The three of them make our Flag… We ALL together make the nation.

Harpreet Kaur Minhas during an interaction with New Castle county TV Channel in April 2017

Jasmine Kaur Minhas and Charanjeet Singh Minhas during an interview with WHYY TV.

April 15, 2017. Walking for peace. Together. Age, color, gender, race or religion can’t divide peace lovers.

God bless those who not only came to participate but came prepared with beautiful messages to make the Peace Walk even more effective and meaningful.

– – – – – – –

MEDIA COVERAGE’S –

This event was covered online by the www.tribuneindia.com on March 17, 2017.

NPRadio coverage of the SAM – www.delawarepublic.org

Recent Comments