by blogadmin | Nov 4, 2019 | Blog Post, Media Publishing's, Sikhism, Year 2019

On 24 October, my wife and I had the good fortune of visiting Kartarpur Sahib gurdwara – before it opens to Indian pilgrims on 8 November.

We travelled from Delaware to Lahore a day before and left for Kartarpur the following morning. There was a lot of construction activity going on, but it was wonderful to get a first look at Darbar Sahib.

What we will cherish most is the kind of hospitality and warmth we received from the Pakistanis, from the security people at the entrance of the gurdwara. We were greeted with warmth and joy everywhere we went. It was a pleasure being at Kartarpur.

We were greeted with a white expanse upon entering the premises. It was amazing to see the commitment of the local and central government in finishing up the work before the inauguration. There was a road being constructed for the pilgrims’ entry, and the library was almost furnished too. The experience was nothing short of surreal.

Construction underway at the gurdwara.

It was most touching to see local people from Lahore and its neighbourhood welcoming and helping us, making sure we had a great time.

This visit was something that we had desired and wanted for a long time, but we’d never thought that such a day would come when we’d have the opportunity to visit the holy destination – that too before the 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak Dev.

We were also lucky to have visited Nankana Sahib, the birthplace of Guru Nanak Dev.

Our purpose in coming here has been fulfilled in a joyous and beautiful way.

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.thequint.com on November 04, 2019.

by blogadmin | Oct 20, 2019 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Year 2019

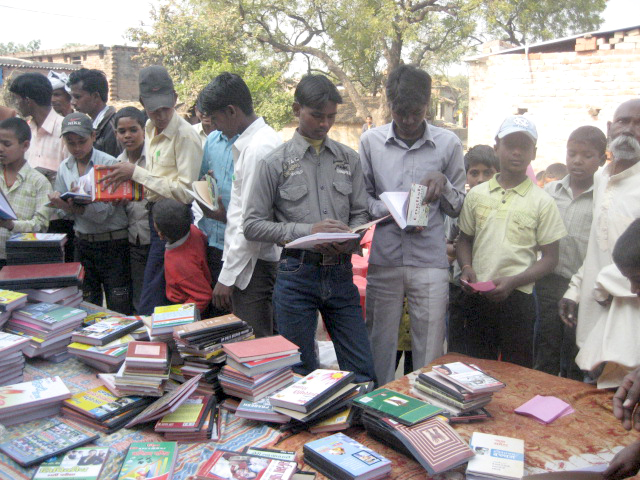

Everyone knows that education is important, but in some parts of the world it is difficult, if not impossible, to come by.

Not many know of two Dover-Camden area Delawareans — Sanjay Kumar and Mahendra Kumar — whose life mission is to change that through a non-profit they started in 2005 aptly named Be Educated!

Like me, the two men (who are not related) were born and educated in India and are in the software industry. I met them nearly 20 years ago when we all lived in Dover’s Woodmill Apartments. I contacted them recently to find out the origin of their educational mission.

Libraries in remote villages

“I was visiting my hometown Lucknow in 2004 where I met Raj Kumar,” recalled Sanjay. “He came along with the vehicle I had hired for my holidays as its driver. He ranted during every single ride about how miserably middle and high school students in rural India do in exams.”

Why? One day, Sanjay finally asked him.

“‘Because the poor and underprivileged in villages can’t afford ‘guides’ (test prep and study materials),” Raj said.

Mahendra’s inspiration was rooted in unfair favoritism and politics. He witnessed blatant and pervasive corruption in the schools. For example, he said, a politician’s son unable to spell his own name was acclaimed over and above other students for academic excellence.

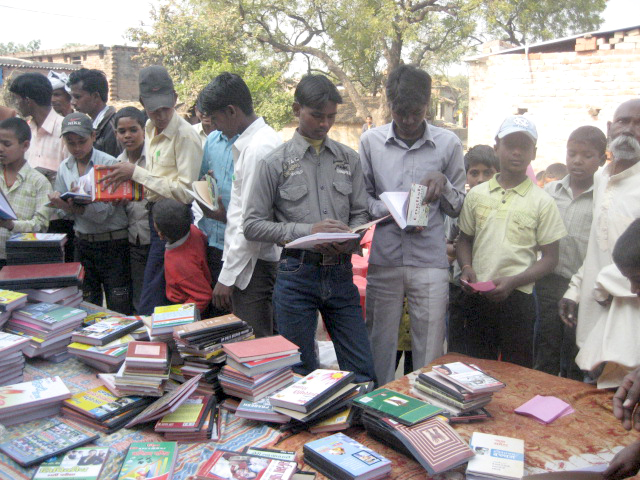

To counter this malaise, Sanjay and Mahendra evolved a simple and economical solution. They opened libraries stocked with study guides in the homes of unpaid, impassioned volunteers in the neediest villages. Each of these $800 libraries was allocated $500 for books and $300 for such necessities as a signboards, cupboards and administration.

The first one was opened in April 2005 in Raj Kumar’s home in Gurubhasganj. The founders were also its sponsors.

By 2007, Be Educated! had opened five libraries in India. Word quickly spread.

Someone in Nepal was very eager to start one there, Raj Kumar reported. That became the sixth library and the first outside India. That same year, another opened in Pakistan.

Today, the nonprofit has more than 80 operational libraries in the three countries. Five libraries each are named after Martin Luther King Jr. and Malala Yousafzai

“How did you choose which villager’s house to open the library in?” I asked.

“We chose those host volunteers who were poor but passionate over the affluent who wanted it as a status symbol,” Mahendra said.

Added Sanjay: “We do ‘Power of One’ fundraisers in Dover. We solicit $1,000 sponsors (the cost has gone up) to open a library in whatever name the sponsor wants. However, the sponsor can’t choose the location. This way we have libraries in Muslim Pakistan sponsored by Hindu Indians and vice-versa. Regardless of how little and humble our endeavor is, we will stay at it to turn the arch rivals into good neighbors.”

Homes for Angels

The program’s success fueled its expansion.

“We started two more projects over the last couple of years,” Mahendra said. “In 2016, we started Home for Angels in Mumbai.”

“Straight from the villages to Mumbai?” I wondered aloud.

Mahendra explained that Kashyap Sanghvi, who lives in Newark, had come from Mumbai. He told them of a couple there who were providing food, shelter, education and everything else to 18 orphans living with them in their two-bedroom apartment — even though they had two children of their own.

“What?” was my reaction

Sanjay picked up the story.

“Exactly! Many of these orphans were children of parents who had died from HIV; some were born HIV positive. This couple, Father Thomas Reji and his wife, took them in because no one else wanted them. They lay discarded on the streets. For help with their education, Kashyap approached us.”

In response the two Delaware men organized a Home for Angels fundraiser in Dover.

“We were clear: only a library isn’t the answer in this case,” Sanjay said. “These kids need space, tutors, desktops, tables and chairs, and, of course, stationery.”

To increase space, the program rented another apartment in the neighborhood and installed video cameras in it. First, only one tutor was hired. A second was added as the number of children gradually grew. They are 32 now, divided into three groups according to age.

“The tutors help two groups with afterschool work every day,” Mahendra said. “The oldest group gets coaching outside, around the corner.”

He acknowledges that raising money for this work is challenging. However, “you are blown away by the magnanimity of the individuals and families. Our tax-exempt status helps,” Sanjay said. “The first fundraiser of $10,000 helped us with renting, decorating and initial ‘goodies.”

“We have angels in Delaware as well,” Mahendra said. He recounted how a Dover couple, after learning that there were no beds for the children, immediately wrote a check to cover the entire cost of 16 bunk beds for the 32 orphans.

Future Girlz

These two men’s latest endeavor is directed at helping Indian girls with their educations.

“Future Girlz is our third project, started in 2017,” Mahendra said. “In this, we open libraries in towns and cities exclusively for girls. Also, in these libraries, learning is measured because we employ tutors to teach and test.”

Why tutor-led libraries with a focus on girls?

“One, they are the neediest,” Sanjay explained. “Two, they love to learn. Third, an educated girl means an educated family, a better world.”

He said the first girls’ library opened in Rajkot in the western state of Gujarat inside an existing women’s center. As with all of their projects, growth has come quickly. There are now six libraries for “Girlz,” including two in Nepal.

If you would like to learn more about any of these programs, contact Mahendra Kumar 302-883-1456, or visit their website: www.beeducated.org.

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.delawareonline.com on October 18, 2019.

by blogadmin | Oct 5, 2019 | Blog Post, Media Publishing's

While growing up in West Punjab, in India, I cannot recall meeting any Muslim other than the art teacher in the boarding school I attended for five years.

What I knew then about Muslims or Islam was based only on TV, movies, and the printed word-almost nothing.

I could say the same for Pakistan, too, even though my mother was born in Karachi.

While I was doing my undergrad in computer engineering in Maharashtra and Master of Business Administration in vilayat later, I met, or rather came across, many Muslims. Nevertheless, these interactions didn’t change anything much for me. I still had not formed an experienced, a deep opinion about the community.

Until recently, I could never think of visiting Pakistan believing that its leaders and people are far from good and that a non-Muslim is hated and is not safe in the country or among them. A good part of my present 20 years in America only strengthened this belief.

Then, I don’t know why or how, things started to change my perspective and understanding about Muslims and more recently, about Pakistan. I wonder, maybe, if it was celebrating my first Eid in 2013 (the great food should also be given due credit!).

I am an interfaith activist here in the state of Delaware where I live and run the software business I started 20 years ago. From my interactions with local Muslims in interfaith meetings, I started to visit the mosques in the area on invitation during Ramadan or for interfaith meetings called in the wake of attacks against Muslims or any other faith community-locally or abroad. The horrific tragedies of New Zealand and Pittsburgh are two examples.

We in the Sikh community partnered with Vaqar Sharief, his wife, Uzma Vaqar, and other Muslims in 2013 to serve hot meals to the homeless and food-insecure residents of Wilmington, Delaware every fourth Saturday of the month, a tradition of service that continues today.

Over time, the relationship with the local Muslim community blossomed. For the last three years I have hosted an iftar for Delaware Muslims during Ramadan. This year I also participated in four others-three by local mosques and one by the New Castle County leadership.

During Ramadan this year, I shared my experiences with the local Muslim community in an op-ed piece in our local newspaper. I explained why Muslims need to be embraced and not feared or hated. They, I wrote, live, love, work, earn, enjoy and have families just like you and me.

My daughter started college last year in Pennsylvania. Her best friends there are all international students from Pakistan. During the spring break, we loved the experience of hosting one of them whose mother back home is a doctor and her father is in the army.

Unlike many South-Asian peers, I am not a cricket nut. In my school and college days I was a swimmer and hockey player. Nevertheless, as a result of my initiatives more than 13 years ago, Delaware today has two T20 tennis ball cricket leagues. In the season that just ended in September after starting in April, 33 teams competed for the two trophies.

My heart fills with joy and my soul with peace to see men of different professions and backgrounds, with roots in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, playing together on the same team regardless of international politics.

Guru Nanak, no less, inspired the evolution of my views about Pakistan. My wife and I wanted to visit Nankana Sahib and Kartarpur Sahib this year to participate in Guru Sahib’s 550th birth anniversary celebrations.

When the word about our deeply cherished desire spread, everyone around us with a connection to Pakistan came forward offering to take care of all of our arrangements from airport pickup to hosting to serving as tour guides.

Delaware resident Shafqat Bhatti’s nephew in Lahore went even a step further when he said, “We too are Sardars.”

“How is that?” I asked.

“I am Sardar Wasim Ilyas,” with the pride of a lion in his voice.

I look forward to visiting Pakistan, and I know we will experience the same love and warmth we have found here in America.

Insha Allah, I promise to share that with you after the conclusion of my visit.

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.dailytimes.com.pk on October 05, 2019.

by blogadmin | Sep 23, 2019 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's

On a summer weekend afternoon, Area 1 of Lums Pond State Park is in the throes of a ferocious cricket battle.

The grand climax of a match is at hand. In the right hand of the bowler at the north end is a ball; in the hands of the hunched batsman at the south end is a bat. And he is intently watching the bowler.

It might have been this batsman’s jutting backside that inspired Oscar Wilde to quip, “I never play cricket. It requires one to assume such indecent postures.”

The bowler starts to run as he delivers the last ball of the match. Suddenly there is pin-drop silence all around. Teams and their supporters become still — there isn’t even air moving through their noses.

The batsman’s mind is focused on scoring more than two runs off this ball. Only that will crown his team with a glorious victory, earning them a place in the coveted semifinals.

At least 100 cricket players visit Lums Pond every weekend during the season since two pitches were added in Area 3. It is time Delaware politicians took notice of the need and potential.

There are two cricket leagues at Lums Pond: The Delaware United Cricket League, which has been around for eight years, and the Delaware Premiere League, which is two years old. DUCL has 15 teams; DPL has 18.

DUCL’s season started in mid-April, and it held its semifinal matches last Saturday. On Sept. 21, at 11:30 a.m., the Lums Pond Cricket Club will face off against the Gujarat Lions in the semifinals. DPL’s season ended last weekend, when the Master Blasters defeated the Delaware Super Kings to claim the championship.

New cricket game formats are growing in popularity worldwide. The days of five-day-long test matches that often ended in a draw are long over.

Maybe George Bernard Shaw hastened their sunset when he said, “Baseball has the great advantage over cricket of being sooner ended.”

There’s a reason why cricket seems foreign to many Delawareans, says Paras Tiwari, captain of the DUCL’s defending champion team, the Lums Pond Cricket Club. The greater Philadelphia area has lost the passion for cricket that it had a century ago. These days, many think it is a game for minorities.

“All those who are playing here are those who were born, and also raised in most cases, in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh or Sri Lanka,” Tiwari says.

Cricket was introduced in that part of the world in the 1700s by the British. A distant cousin and forerunner of American baseball, it remains England’s national sport.

Some of Delaware’s cricket-crazy immigrants wish there was more local support in building interest in the sport.

“Why is cricket not introduced in schools?” asks Sunil Prashar, an all-round cricket veteran and DSK’s leading light. “Our own children — forget those who have no cricket in families — can’t learn the game without that.There is no academy in Delaware like in neighboring states. There is no indoor facility in Delaware like New Jersey has. That restricts the game to only a few months in a year.”

Major Minhas, who is one of DUCL’s main organizers, agreed that lack of facilities is a problem.

“We don’t have enough cricket pitches to play,” Minhas said. “One of the reasons why I supported Matt Meyer’s election was he promised one or more cricket pitches (cricket fields) in the county parks. But nothing so far.”

America has a closer history with cricket than you might think. Former President Ronald Reagan, who was “addicted” to cricket, thought it was “Buddhism made visible.” He was fond of using cricketing imagery and lingo.

“He also once said … that the most dangerous thing in the world, after Communism, was a rising ball outside the off-stump,” one former adviser was quoted as saying.

Cricket allowed Reagan to cozy up to Margaret Thatcher — unbeknownst to him, she knew a duck (zero in cricket) about cricket.

If you’re looking for something different, come and take in one of the cricket matches at Lums Pond. Perhaps you’ll even learn some of the sport’s terms that intrigued a former president: silly point, fine leg, short leg, slip, gully, googly, silly mid-on and silly mid-off, just to mention a few.

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.delawareonline.com on September 19, 2019.

Also, published in Newspaper on September 21, 2019

by blogadmin | Sep 6, 2019 | Blog Post, Media Publishing's

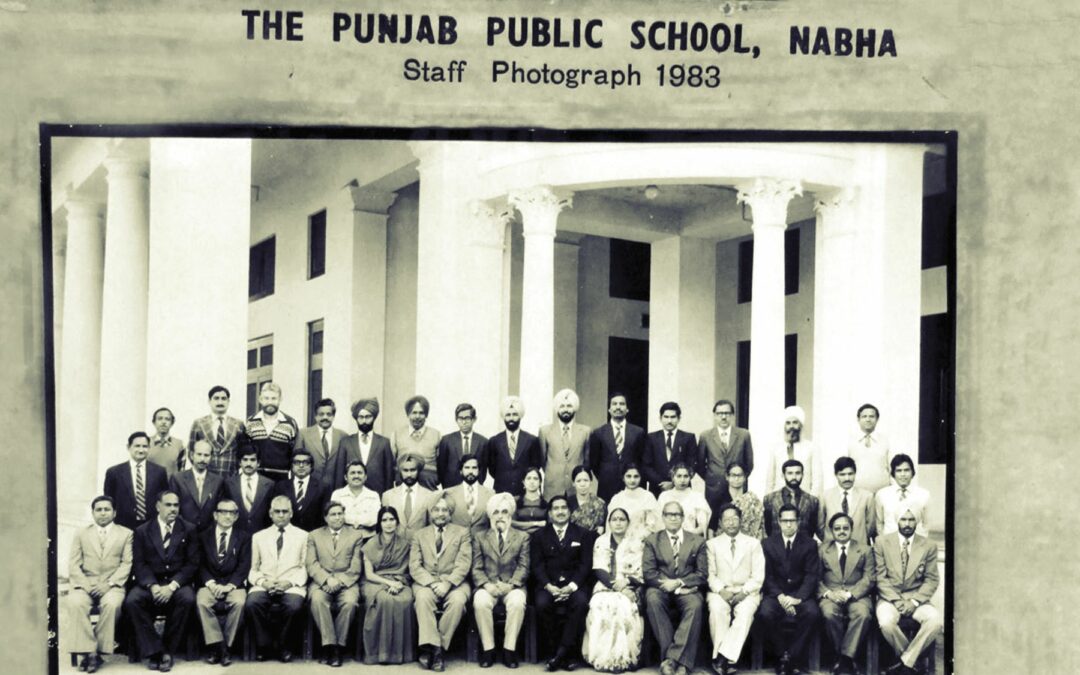

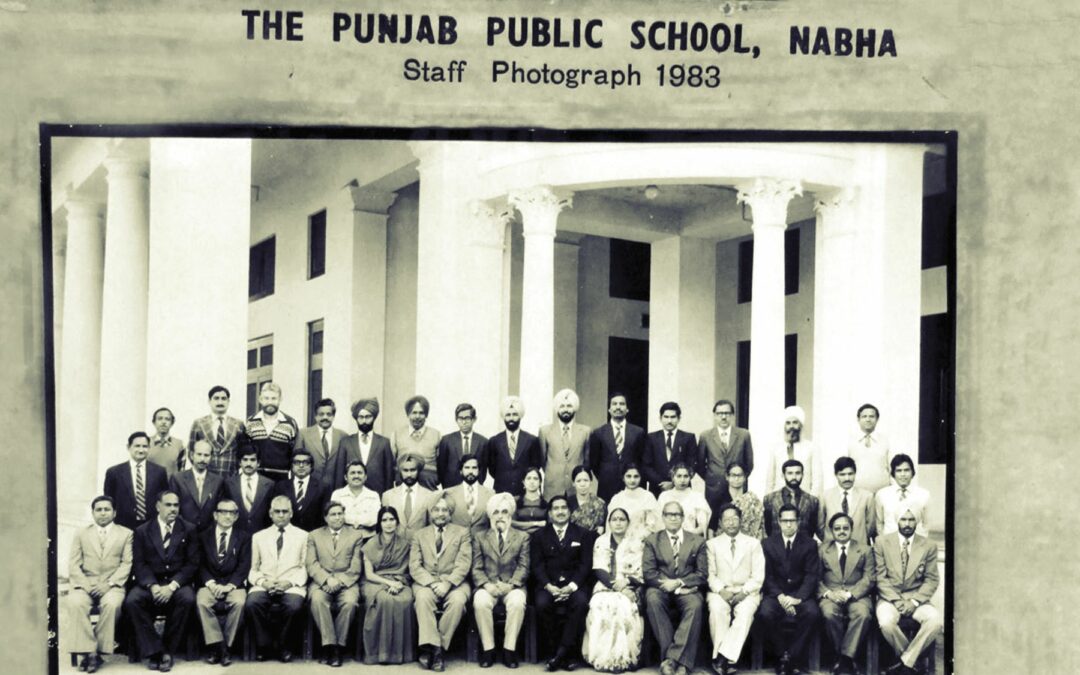

The Punjab Public School (PPS) in Nabha, is a great institution for reasons beyond its enviable infrastructure and stellar alumni such as Indian Army General Bikram Singh, or Hero MotoCorp Managing Director Pawan Munjal, or Wharton professor Jagmohan Singh Raju.

I was a student here for five years, beginning in August 1980. Most of the school’s success must be credited to its teachers, including founding headmaster JK Kate. One such teacher who must be given his due is KMP Menon; he taught economics.

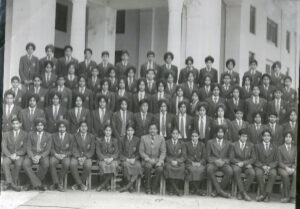

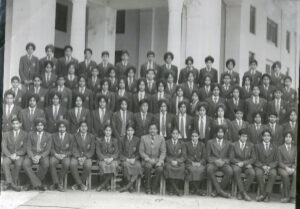

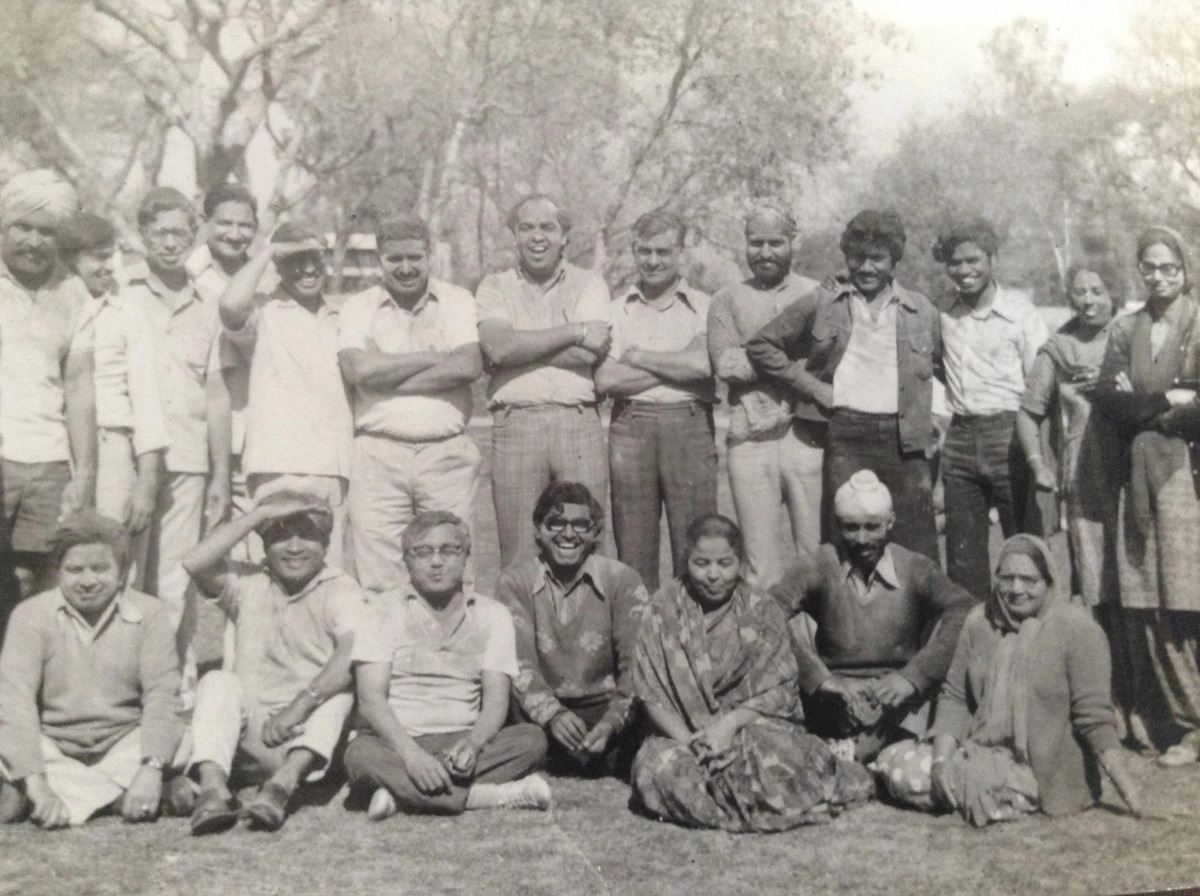

Beas House picture (Mr Menon, with senior Beas House as its housemaster; sitting in the center, in this 1986 picture).

Several of Mr Menon’s students remember the way in which he reached out to them in times of desperation. They always reiterate how Mr Menon offered his help with love and grace. Even in the classroom, his approach to teaching economics was unique. I can vouch for this even though he never taught me. I had only experienced him when he came as a substitute teacher to my class.

I was in class 9. “How many of you know that Nizam of Hyderabad was the world’s richest man in his time?” Mr Menon had asked the class.

What he went on to narrate has never left me since that day in 1984. “Here is one of the ways in which he became the wealthiest: The Nizam was a smoker. He loved smoking expensive cigars. However, his frugality didn’t allow him to spend on them. Can anyone guess how he still enjoyed the most expensive cigars without spending a paisa on them?”

The clueless class looked raptly at his dark and calm face who wore a thick mustache, with curly hair nestled atop his head.

“He smoked the remainders his guests left in the ashtrays!”

I retold the story to a few visitors in Bangalore on 17 June 2015, as I sat by the bed of an unwell Mr Menon. My audience included my PPS companions, Naveel “murda” Singla and Deepak “thakur” Singh, in the room of the teacher’s younger daughter Mini’s house. Mr Menon squeezed my right hand after I finished: “You still remember that,” he said in a whisper, as tears streamed down his face.

As we were leaving, Mrs Menon stopped us and gave us a message from her ailing husband: “Waheguru Ji Ka Khalsa Waheguru Ji Ki Fateh!” This time, I couldn’t hold back the tears.

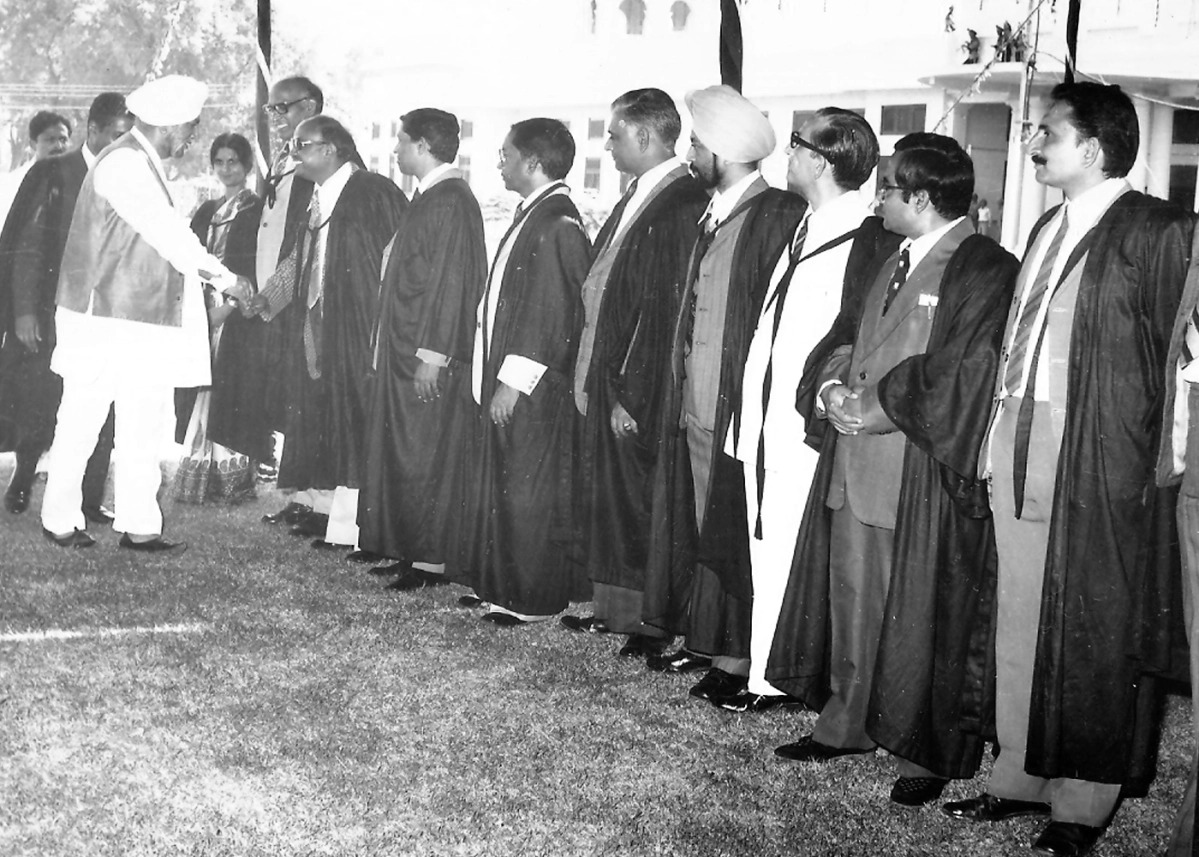

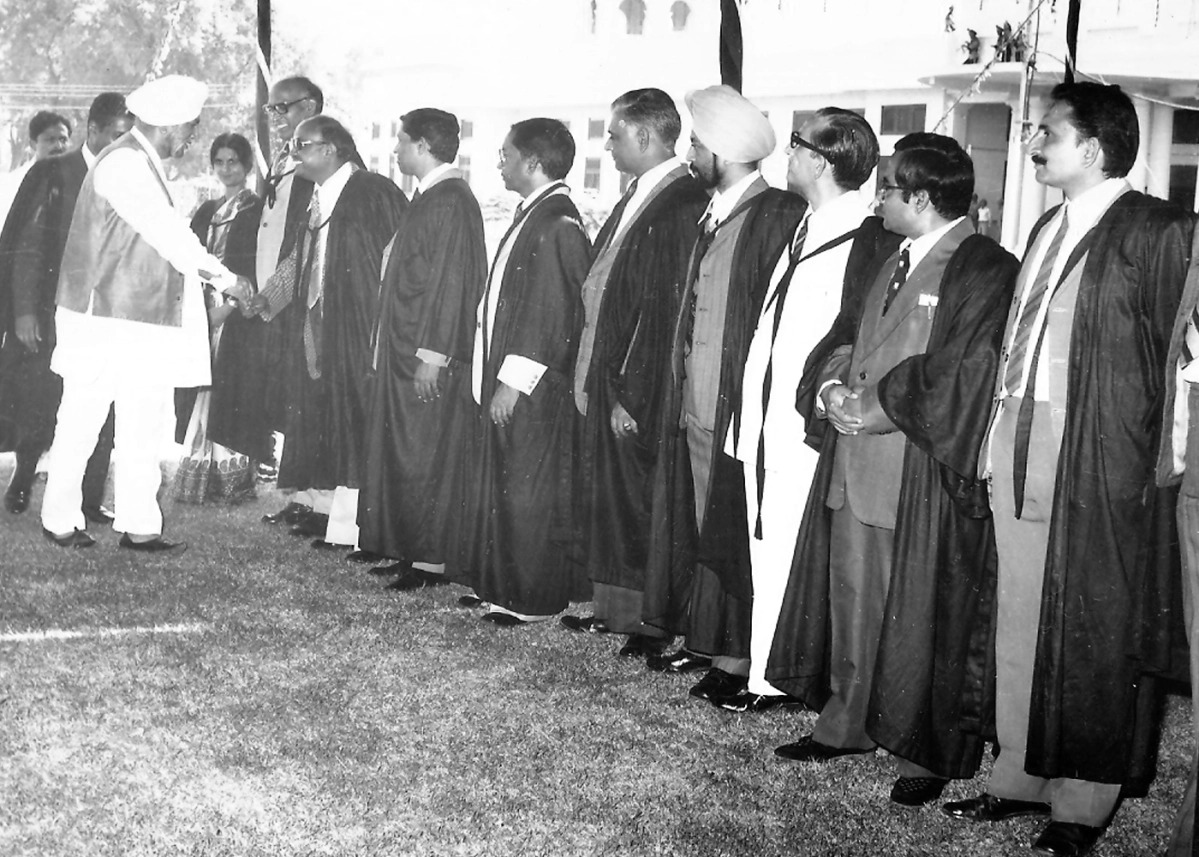

The school Headmaster, Mr. Manjitinder Singh Bedi, an old Nabhaite himself, is introducing the Founders’ Day chief guest to Mr. Ram Singh.

Mr Menon, the “Kindest Father”

Until then I had not understood how seriously ill he was. The following evening, as I had just started to sip my whiskey, the phone rang. It was Mini. Her father, Mr Menon, had passed away a few hours ago. I was in shock.

Mini also commented that after our visit the previous day, “Mom said your visit had brought a divine calm and joy on his face she had not seen in a long-time.” Both his daughters, Mini and Mickie, are still not “in a space to even have a photo of him in the house.”

Mr. Menon with his wife and two daughters visiting Golden Temple in 2017.

Said Mini of her father: “…kindest, most intelligent…the words dislike or hate never existed for him…had the most amazing Wodehousean sense of humor…I changed forever the day my dad left me. He wouldn’t have liked it at all. But that (is) the downside of having the perfect person as your father…”

How We Earned Our Nicknames

Another teacher in this legendary league was Mr Ram Singh.

Though I can’t say how many inches over four feet he was, he towered tall, and not only for those he taught mathematics to. His “kakaji” shouts echoed through the senior Jumna House for which he was housemaster, even in the winters — his well-known ‘enemy’.

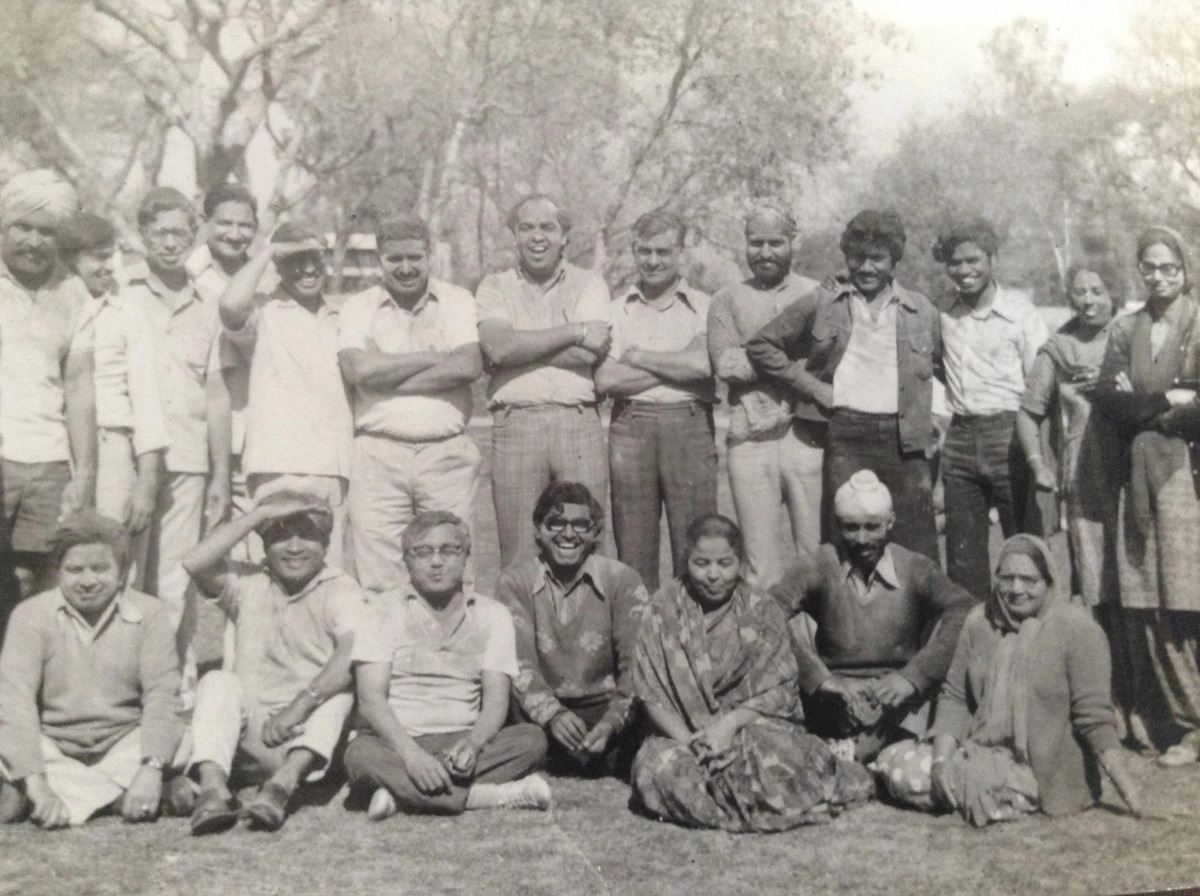

Mr. Ram Singh sitting third from left. (This picture was taken during the P.P.S. staff colony Holi celebrations in the late 1970s)

All of us in the school, especially the overwhelming majority who were boarders, were soon given nicknames by our peers, upon joining the junior school in classes fifth or sixth. My friend Rajesh “panditji” Sharma, who lives in Brampton, Canada now, was gifted his ‘middle name’ by Mr Ram Singh.

“Since I joined the school in eighth along with our Appu brothers, Rahul and Ashish, Mr Ram Singh asked me my name in the math class. When I told him, he went, “Oh, so you are panditji,” and that was that. Hardly anyone knew my real name, and that stays true till date. “A few of my neighbors here call me that because they have overheard my wife using it at times,” Panditji told me over a phone call on 4 July.

During Founder’s Day celebrations, Senior Master, Mr. Y. P. Johri, introduces the chief guest. Mr. Ram Singh is second from right, clasping his hands together over his belly.

Mr Ram Singh: A Stickler For Honesty & Integrity

I was home enjoying the American Independence Day holiday that Thursday. When I checked our ICSE ’85 WhatsApp group, I saw that Panditji had posted, informing us of Mr Ram Singh’s passing,

“Here goes another pillar,” I mumbled, and heaved a deep sigh.

Though Mr Ram Singh retired ages ago, he still lived in Nabha in a rented house with his wife. His only child, Pappu (Abhijeet Singh), lives in Sydney, Australia, with his wife.

Mr. Ram Singh in the middle in black glasses, with his wife and three former P.P.S. colleagues and their families. An early 2013 picture.

Shivraj Singh “Binnu” Brar, presently security chief of the State Bank of Patiala, after his retirement from the army, also has stories about Mr Ram Singh, who was his Jumna House housemaster.

“It was raining one day when Mr Ram Singh came into the house for a random tour when there was almost nobody in the house. He closed his umbrella and left it standing top-down against the wall of the entrance. We put it high up somewhere. When leaving, he could see it but couldn’t reach it.”

Binnu was good at many things, but academics was not one of those.

“Mr Menon was too good. Once I was trying to cheat in an exam and he was on duty in the exam hall. He came and gave me the book itself. When that didn’t end my struggles, he helped me find answers. With Mr Ram Singh it was slightly different. Once I copied Sukhwinder Singh “Sukhi” Grewal’s answers during our mathematics exam. When we got our papers back, Sukhi got 90, and I, only 45,” said Binnu, who had, at the time, indignantly gone to Mr Ram Singh with his grievance.

“If you can, right now, do even one of them correctly, I will give you 100,” Mr Ram Singh shot back.

Mr. Singh with his wife, son, daughter-in-law, son, and grand daughter in this December 2017 picture

How Two ‘Outsiders’ Stayed Back to Teach in Turbulent Punjab

“Mr Ram Singh had a special place in his heart and mind for farmers’ children. He went out of his way to help them and cajole them into doing something. I was part of the school band. Rumor has it that you had to at least fail in three subjects to qualify in the school band,” Binnu said. “Mr Ram Singh would tell some of us from the villages, ‘at least go join the school band.’”

While Mr Menon was from Ottapalam in Kerala, Mr Ram Singh hailed from Allahabad – in fact, Amitabh Bachchan’s dad taught him English when he was in college at Allahabad University. Their roots help explain why these two teachers are so revered. Punjab and the Punjabis were hapless victims of the senseless violence in the 1980s. These two “outsiders” stayed on to take care of and support us even when many Punjabis left in search of peace and security.

How can a school or its students ever repay such luminaries?

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.thequint.com on September 04, 2019.

by blogadmin | Aug 15, 2019 | 88to92 Engineering Batch, Blog Post, India, Media Publishing's, Year 2019

An event that took place in 1989 remains etched in my memory. It isn’t the first liver transplant or Sachin Tendulkar’s international debut. No, it’s also not about the fall of the Berlin Wall.

It is about an evening during my computer science undergrad second year at the BN College of Engineering, Pusad, and the college’s then Principal BM Thakare — popularly known as ‘Takla’ among the students.

Rain had engulfed the town and lightning was ripping apart the skies, when Gurminder, Chauhan, and I finally left the Mungsaji Bar — past its closing time. We walked towards the parked cycle-rickshaws outside and enquired: “Eh bhau, engineering college hostel?”

We broke into riotous laughter along the way in the rickshaw, while imitating Nana Patekar’s dialogues from Parinda — a film we had watched earlier that evening. Upon our insistence, bhau removed the rickshaw’s hood from over our heads.

The Terror That Was Principal Thakare

I don’t remember why and when we shifted gears and started to sing. But I remember us loudly singing Shalimaar’s song Hum Bewafa, when we approached the house of Principal Thakare, unaware of our surroundings until my more-academically inclined companions noticed it when the house came into sight, and panicked. The house stood alone, away from the road, between the bar and the hostels.

Their panic only made my Jinga Lala Hur Hur howling louder. Just then two long bursts of lightning illuminated a car backing out of the house. Seeing that even I panicked.

Our worst fears came true. The car screeched to a halt before the rickshaw and the principal jumped out of it. We almost stopped breathing and reluctantly got off the rickshaw, scared out of our wits.

“What’s wrong with you hooligans? Why are you all braying like donkeys in the middle of the night?” This wasn’t the thunder from the sky. We exchanged looks amongst ourselves with furrowed brows.

“We? No, no, sir…we…we were just discussing if Gurminder and Chauhan will get a scholarship for jointly topping the first year,” I said.

“Who was making a lot of noise on the road then?”

“Couple of other rickshaws go…” Gurminder fumbled with words.

“Four college boys… on a bike, sir,” Chauhan said, pointing towards the hostels.

“Many seniors just went past us, sir,” I chimed in. We started to breathe again when Principal Thakare got back into his car. That’s the kind of terror Mr Thakare elicited from both students and staff.

A Lesson In Humility From Principal Thakare

He was the principal of the college from its inception in 1983 until 1996, and then stayed on as director for the next ten years, before moving to Nagpur for good. The rickshaw caper was not the only incident that showed Mr Thakare’s authority and persona.

Sandeep Chahal from Rohtak had just joined the college’s civil engineering course in 1990. A few months later, he and his friends were caught by the hostel warden drinking, dancing and peeing on the hostel roof. They were all summoned to Mr Thakare’s house the next day. It was a Sunday.

“He scolded us, shouted at us, and asked, ‘Should I rusticate you all or give you a chance?”

Sandeep quotes Mr Thakare often when he addresses the student community of the college he runs in his hometown now.

“Principal Thakare kept pacing back and forth in the verandah of his house like a pendulum while we stood below looking bloodless. No one was breathing. After a gap of every two oscillations, he would reach the switchboard and press a button, first on and then off. I stood there reminiscing Sholay’s Gabbar Singh, but singing Maar Diya Jaye Ki Chhod Diya Jaye Bol Tere Saath Kya Slook Kiya Jaye in my head,” Sandeep recalls.

One of Sandeep’s accomplices was Anil Rathee. He was a rebel, in love with trouble. His experience with Mr Thakare was a bit different.

“When I joined the college back after one-year rustication, I was determined to prove Mr Thakare’s saying, ‘you will never pass,’ wrong,” said Rathee. “After graduation I went to meet him.”

“Do you know why I had rusticated you?” Mr Thakare asked him.

“Because of what I did.”

“No, to teach you how important it is to be humble. Life humbles everyone.”

Principal Thakare, The Disciplinarian

Sometimes Mr Thakare’s lessons were a bit more forceful, as Sanjay Grover found out. Sanjay was a year junior to me in the college. He was academically better than his circle of friends. Initially, he used to help them cheat. One day, while walking towards the canteen, he made an about-turn upon seeing the principal heading in his direction.

“Mr Grover,” Mr Thakare called out.

“Yes sir,” Sanjay meekly answered.

“Change your friends and habits,” he said calmly, “and stop doing what you are doing.”

“I don’t understand, sir,” Sanjay replied, applying the ignorance is bliss theorem to the problem at hand.

“Let me be clear, Mr Grover. You are on oxygen and guess who controls the supply? Before Sanjay could answer, Mr Thakare said, “ME!”

How BM Thakare Built An Institution & A Community

As former students recalled their “teaching moments” with Mr Thakare, the faculty remember his commitment to the college. Mr KR Atal taught us mathematics in the first two years. He described how the college evolved from just a badminton hall to what it is today because of Mr Thakare’s vision and work ethic.

“Even in only the badminton hall days, the college’s functioning was smooth,” he said. Later, all classes, labs, library and offices were moved to the current workshop building once it stood up. Mr Thakare was the first one, every day, to reach the college on his scooter. He would greet and welcome students and staff when they entered. All this when he was often the last one to leave.”

His dedication inspired countless former students, even long after graduating, to become Principal Thakare’s ardent followers.

Thousands in India and hundreds spread across the globe felt obliged to visit him in Nagpur whenever possible, and took pride in posting their pictures with him on social media.

Principal Thakare was overwhelmed by the respect and gratitude, as the tears in his eyes often revealed.

The Devolution Of BM Thakare’s Grand Institution

His ability to build an institution extended to the community. Besides overseeing the affairs of the institution and teaching final year civil engineering students, I cannot understand how he still managed to regularly appear everywhere: from the hostels, the mess halls and college canteen, to private houses rented outside by the students.

The college was booming in those years and he loved steering its growth. Each year saw new additions. From hostels to classes to tennis courts and an administrative block, library, and auditorium — all grew under his direction and supervision.

The college of the time was a multicultural, multilingual and multicoloured garden in full bloom.

No wonder the remote and impoverished Pusad taluka was benefiting from it in more ways than one.

Responding to the growing demand, many new shops, lodges, restaurants, and bars opened up in Pusad. A beautiful garden park also was added between sootgirni and the college. I was still in the college when the local MLA, Sudhakar Rao Naik, became the state’s chief minister in 1991.

I visited the college briefly in 2013 and found that everything had changed. Though the whole college had gathered at the state-of-the-art auditorium to greet me, barely half the room’s capacity was filled. I couldn’t oblige the students when they asked me to speak only in Marathi — not Hindi or English.

Principal Thakare’s Demise: ‘Losing A Mentor, Teacher… My Pappa Ji’

The college looked like India’s concrete jungle metropolis, sans traffic. The empty hostels and near-empty classrooms were sulking—not so silently. Contrast it with my time, when three of us were packed in each hostel room designed for only one.

Pusad, too, had nothing uplifting to offer. A lot of bars, restaurants and other outlets I frequented in my time had died. Sootgirni had closed. The Naik family’s influence, the town’s crowning glory, was rapidly evaporating.

Last year, in Vancouver, I organised an alumni reunion of college students. Someone whispered that the college would soon close because it was struggling with admissions.

I am sure principal BM Thakare knew the state of his “child” only too well. How could he stay to sift through its ashes?

He passed away in the wee hours of 14 July this year.

Thousands of his former students’ messages like this one from the current principal, Avinash M Wankhade, on Facebook, reflect what they felt: “Today I am speechless…feeling alone…I lost my best teacher…I lost my mentor…I lost my PAPPAJI.”

Recent Comments