by blogadmin | Nov 12, 2018 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Year 2018

It was the Saturday after — the first Shabbat service in the aftermath of the Pittsburgh tragedy was about to begin.

Sunmeet Singh Sethi and I entered the local synagogue here in Newark, Delaware. Rabbi Jacob Lieberman, a short, handsome man wearing a kippah, like many others in the congregation, stepped off the dais to welcome us.

After returning to the lectern, the rabbi’s hands rose repeatedly to clean his cheeks. Then he left.

I noticed other congregants turning their necks to look at us with grace and kindness. He reentered after a couple of minutes and looked at us and others. He was still crying.

Growing up in Punjab and studying and working in India, America to me, and those around me, was a mecca of creative and constructive activities — a land of opportunities. No wonder, then, that an army havaldar’s son could dare think of starting a software company immediately after landing here in 1999.

Related: Pittsburgh shooting is a blow against the very soul of America

A 97-year-old, an elderly wife and husband: These are the 11 victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre

That company, Tekstrom, will celebrate its 20th birthday next May.

Even the sky wasn’t the limit in America, or so we all believed. Americans had literally proven it by landing on the moon a year before I was born.

The assembly line, harnessing the atom, developing the computer and creating the cyber age — America had revolutionized the world on many fronts.

For someone who dreamed of coming to this country, and worked hard to make it happen, it has been especially painful to witness the hatred expressed by a tiny, but lethal, group of individuals in this country.

Six years ago, it struck a gurdwara in Oak Creek. Recently, a synagogue in Pittsburgh. In between, a black church in Charleston.

All three tragedies were perpetrated by lone white supremacists; all three at places of God; all three at an interval of three years.

In each case, the perpetrators’ numbers rose: six victims the first time; nine the second; and 11 in Pittsburgh. And, then there were the additional tragedies in schools across the country, the concert in Las Vegas, the nightclub in Florida, among others.

Sunmeet and I were at Temple Beth El to express our love and solidarity with the Jewish community. We were there to share their unspeakable grief that resulted from the unconscionable desecration that occurred the preceding Saturday.

The sinking feeling I had after hearing about the Oak Creek shooting is still fresh with me. I was in Bangalore that day visiting my India operations with my wife and two children. Renu and I were worried especially about our son. He was then, and even today, the lone Sikh boy with long hair to ever attend his private school in its century-old history.

Every Saturday he has a private lesson with his violin teacher at her house, a place my family knows well from the many Passover dinners we’ve enjoyed there. That day I dropped my son off for his Saturday lesson and went to the gym.

It was there, on the wall-mounted TV-screens, that I learned of the tragic Pittsburgh shooting. It triggered that familiar sinking feeling once again. I thought of my Jewish friends and their pain and anguish.

The next day I joined hundreds of others gathered at a vigil on the steps of Memorial Hall at the University of Delaware in Newark. We had assembled to express our solid rejection of the anti-Semitic hatred that infected the shooter who wanted to “kill all Jews.”

Addressing the gathering, which included representatives of many faiths, Rabbi Lieberman had this to say: “For our grief, this is an opportunity to mourn. For our outrage, it’s a time to cry out. For our fear, an opportunity to pray and to invite courage, and for our vulnerability, it’s a time to stand with others and to discover that we are not really alone.”

Others spoke as well. “Today, we are not Catholic, Protestant, Buddhist, Muslim [or] Hindu,” U.S. Senator Tom Carper said. “Today, we are all Jewish.”

Delaware Congresswoman Lisa Blunt Rochester, Gov. John Carney and many others who spoke mentioned virtually all religions except Sikhism. It was only U.S. Senator Chris Coons who reminded the crowd of the shooting at the gurdwara in Wisconsin.

I’m sure the officials’ omission was not intentional; we are a tiny demographic in America compared to other religions, but passing Sikh Awareness Month resolutions (April) in the Delaware legislature that I started in 2017 must go on for many more years, I resolved.

When Sunmeet and I walked to the parking lot that Saturday after the Shabbat service, a woman stopped her car near us. She was in tears. She blew kisses at us while saying, “Thank you for coming!” Sunmeet later told me that two of her loved ones were among the eleven victims in Pittsburgh.

A reminder of how far we all need to go to expand our understanding came when a couple of Sikhs questioned me for going to the Shabbat service, just as many Sikhs and others ask me every year why I host Iftar dinner during Ramadan. Others question my celebrating Christmas, Diwali, Lohri, Holi, Passover and other festivals.

“Why not?” I reply.

“You are a Sikh.”

“Precisely. I only feel Sikh when I am doing this because my Nanak’s blessing of ‘Sarbat Da Bhala’ hugs me warmly and blissfully only during such moments.”

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.delawareonline.com on Nov 9, 2018.

by blogadmin | Nov 8, 2018 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Year 2018

IT was the Saturday after. The first Shabbat service in the aftermath of the Pittsburgh tragedy was about to begin. A friend and I entered the local synagogue in Newark, Delaware. Rabbi Jacob Lieberman, a short, handsome man, stepped off the dais to welcome us. After returning to the lectern, his hands rose repeatedly to his face. Then he left. I noticed other congregants looking at us with kindness. He reentered after a couple of minutes and looked at us all. He was still crying.

Growing up in Punjab and working in India, the US to me, and like others, was a land of opportunities. No wonder, then, that an Army havaldar’s son could think of starting a software company immediately after landing there in 1999.

It has been especially painful to witness the hatred expressed by a tiny, but lethal, group of individuals in this country. Six years ago, it struck a gurdwara in Oak Creek. Recently, a synagogue in Pittsburgh. In between, a black church in Charleston. All three tragedies were perpetrated by lone white supremacists; all three at places of God; all three at an interval of three years. And then, there were additional tragedies in schools across the country, the concert in Las Vegas, the nightclub in Florida….

My friend and I were at Temple Beth El to express our solidarity. The sinking feeling I had after hearing about the Oak Creek shooting is still fresh with me. I was in Bengaluru that day, visiting my India operations with my family. My wife and I were worried about our son. He was then, and even today, the lone Sikh boy with long hair to ever attend his private school in its century-old history.

He has private violin lessons in a neighbourhood we know from the many Passovers we have enjoyed there. That day, I dropped him and went to the gym, where I learned of the Pittsburgh shooting. It triggered that familiar sinking feeling. I thought of my Jewish friends and their pain. The next day I joined hundreds gathered at a vigil in Newark. Addressing the gathering, including representatives of many faiths, Rabbi Lieberman said: ‘For our grief, this is an opportunity to mourn. For our outrage, it’s a time to cry out. For our fear, an opportunity to pray and to invite courage, and for our vulnerability, it’s a time to stand with others and to discover that we are not really alone.’

Later, a couple of Sikhs questioned me for going to the Shabbat service, just as many Sikhs and others ask me every year why I host Iftar dinner during Ramadan. Yet some others question my celebrating Christmas, Diwali, Lohri, Holi, Passover and other festivals.

‘Why not?’ I ask.

‘You are a Sikh.’ I am told.

‘Precisely. I only feel like a Sikh when I am doing this, because my Nanak’s blessing of sarbat da bhala hugs me warmly and blissfully only during such moments.’

– – – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.tribuneindia.com on Nov 9, 2018.

by blogadmin | Sep 2, 2017 | Blog Post, Media Publishing's, Year 2017

My father joined the Indian Army in 1948, a year after British India was sliced in two. The earth around him shook, not from the impact of five rivers, but from the numerous blood rivulets that flowed through the furrows of the Punjab’s fields, bazaars, children’s playgrounds, and streets and gushed from the Punjabi homes’ brick drains. It was alleged that it was the climax of the English colonial chess stratagem: Divide and Rule.

“Why did the earth shake?” I remember asking him some years after he had retired.

“Freedom fighters worshipped Mother India and gave their blood and lives as an offering to her,” he said, “but there were others who never took any pain in doing anything for the country — and had enjoyed their time behind the cover of religion. When the British decided to free India, these religionists forced a historic paradox: freedom fighters, dead and alive, were defeated by their own countrymen, by these religionists who were determined to operate on the mother and create another one out of her.”

“How did they do it?” I wanted to know. He didn’t answer for some time.

“August was running as always but this time, just when it reached the middle of its run when forefather Time raised both hands and united them, the Mohammeds and the Mahatmas and the Pandits of British India began the surgery to create two mothers from one. They started to amputate the body parts of the existing mother. However, they took care of only those parts they had a sense of belonging to. They only put those areas under the knife that had already been donating blood for the country,” my father replied, voice breaking.

“Why didn’t the Punjabis and Bengalis take precautions?” I asked wisely.

“We are one people, one country, we were told by them through powerful and seductive slogans that proved to be empty rhetoric,” he responded. “We were asked to stay put in our homes in the warmth and security of our ancestral places. Then, suddenly, the surgery began: no anesthesia, no tranquilizers. The separation started, and with it came the rapes, looting, and macabre killings, and we could see the remnants of hundreds of thousands of our people lying strewn about by the time it was over.

“In a matter of hours and days, kaka, millions were made refugees, tens of thousands were raped, and hundreds of thousands were killed. Grandfathers, fathers, and brothers were so helpless that in some cases, in acts of mercy, they themselves killed the women of the family. It was a pain those leaders never felt and the world has been never told about.”

The successors they mentored corrected the mistake by slicing it again to create the third mother in 1971-72. English and the “Divide and Rule” doctrine had certainly survived, even though the Englishmen had left.

If you thought that was enough, no; they weren’t done yet.

One of India’s Prime Ministers, their progeny again, almost succeeded in slicing the mother country yet again. Thirty-seven years later, while justifying a state-sponsored Sikh genocide to avenge his mother’s assassination, Rajiv Gandhi said, “When a big tree falls, the earth shakes.” That the “Divide and Rule” was clearly on his mind, before and at the time he said it, and on the minds of the coterie around him, was clear from the election results. 1n the December 1984 polling, only six weeks after the Sikh genocide, Gandhi’s Congress Party won a thumping majority of 404 out of 533 seats.

Whenever my father narrated the partition tales, he would invariably say, “When the British freed India…” That was different from blood-stirring tales of freedom and struggle I had read about and heard in speeches on TV. Thinking about it later made me curious, and I decided to do some research. It didn’t take me long to understand why he said what he said.

The colonies in Asia and elsewhere were the result of European imperialism. The two world wars in the last century had weakened them economically. The wars also produced the arrival of two more giants on the global scene: the United States and the USSR. The Second World War also shattered the impregnability aura that had haloed the British Empire earlier. The defeat of colonial powers by Nazi Germany at many places had fatally undermined the myth. Japan took over colonies in Southeast Asia during the war. In many colonies, as in the case of India, too, the rulers had made promises of independence to nationalists in return for their help in the war.

India’s first Sainik School (changed into a public school soon after) founded in Nabha was the result of such economic inducement promised by the British to Punjab in exchange for military recruitment. I know because I went to that boarding school. The Punjab Public School (PPS), established in 1960, is widely known today for sending most commissioned officers — outside of RMS, Dehradun — to the Indian armed forces.

On June 2, 2012, I hosted a very well-attended reunion in Delaware of PPS alumni from across the United States, Canada and India. At that time, PPS’s first alumnus became India’s army chief. The newly minted Gen. Bikram Singh called in from New Delhi to thank the alumni and add to our festive spirit.

Here, in this school, I lived, played and studied with students from J&K, UP, Bihar, Bengal, Assam and many other parts of India. The school sent me regularly on travels and treks to many far-flung places in India — both remote and metropolitan. Providing us students with opportunities to learn from adventure and acclimatization was the school’s underlying mantra for a classy education.

The hymn made a home in my heart. No surprise, then, that my Bharat darshan continued after PPS. I enjoyed living in different parts of India for work, studies, and business, and, in the last two decades, showing my US-born children one of the oldest civilizations on the planet.

It is my love for this land even with its open sewers beggars—that I still remain its citizen so many years after I became a permanent resident of the US. The US is a great country and I love it, but cannot abandon the mother in whose lap I was raised.

Earlier, when I was single, and after I returned to India from the UK with a master’s degree in business to complement my computer engineering studies, I worked in Bangalore and Hyderabad before coming to the US in 1999. Tekstrom, the software testing company that I founded on arrival presently has a campus in Bangalore.

My conclusions from long and wide-ranging experience tell me that the English still rule our nation even though there are no English in India’s government, parliament, and judiciary. If anything, the inequity has become more rampant and flagrant. The mental slavery still persists. An Indian is happily obsequious to a white while he finds it back-bending to respect a colored. This is not only on display back in India but is visible among migrated Indians here in the US as well.

A few months ago, the governments of 40 African countries condemned the Indian government for the growing racial and xenophobic attacks on Africans in India. Let me remind you that the imperialism of the past which India is celebrating its 70th year of independence from was similarly racist.

To put our independence, and its track record since 1947, in perspective, remember that India was once solidly against apartheid in South Africa: something for which India paid a heavy economic price. Recall Mahatma Gandhi’s South African sojourn!

At 70, we are no longer an infant democracy. However, we are still like that elephant, the one India has historically been compared to, the elephant that moves slowly because it is carrying too much potential. Since independence, its movement is becoming even slower, perhaps because the untapped potential is becoming larger.

Except in cricket, the game the Englishmen gave their colonies, including India, we have no commanding presence in any sports discipline. During the Raj, we were undisputed world field hockey champions. The two Noble prizes we won during the Raj were in Literature and Science; and far less apart from each other are the two we won in the last 70 years — both Peace Prizes. We are still ignorant of punctuality etiquette and that is true of Indians regardless of where they live. We are never in a hurry to fulfill our promises.

Justice is almost at a standstill in India despite the fact that India supplies the largest pool of computer software labor to advanced countries. During colonial rule a case used to be decided in 10 years. Last year, chief justice of India, Justice Thakur, lamented that, “Now, cases and litigation have increased. People’s expectations have also gone up. It is all becoming very difficult for us and this is why I have repeatedly urged them (government) to pay attention to these problems.”

To make the matters worse, law and order is almost absent in India. Who knows better than the NRIs whose properties in India are always greedily eyed by unscrupulous elements? In my case, someone occupied a vacant plot my father had bought in Punjab decades before he passed away, and my continuing ordeal to vacate the completely illegitimate occupation by total strangers is beyond the scope of this piece.

The powerful can get away with threatening, looting, raping, beating, and killing. Perpetrators of 1984 Sikh genocide still haven’t been punished. They have been honored, given high positions, and publicly feted. We are still not a casteless society as was envisaged. It is still either a curse or an entitlement depending on the last-name of the parents who gave you life.

Gender discrimination is practiced at all levels almost openly. Some parents still advocate killing a female child before or after birth. Many have experience doing it. The instances of rape and rape threats are increasing at an alarming rate. Even when the daughter of an army officer killed on the border dares to speak, she is openly threatened with rape. It is alleged that the present ruling party has an exclusive troll army to beleaguer and threaten those who dare to speak against them and their policies. A husband or boyfriend may incur the ire of India’s “morality brigades” if they even hold their partner’s hand in public. When watching a movie those who don’t get up in cinemas when the national anthem is played may be in for a “quick lesson” in patriotism.

Only law enforcement and bureaucracy match the media’s probity in India.

With disappearing internal security, the security at the borders too has become iffy. Pakistan-sponsored jihadis easily sneak in and indulge in violent activities and inciting violence. Their penetration and reach is growing deeper with time. Their attacks have ranged from J&K to the parliament to hotels and bakeries. More recently they have blatantly attacked military bases and city police stations.

Our ongoing historic feud with Pakistan has cost us dearly in many ways. And if our ability to contain tiny Pakistan is an indication, imagine our future with colossal China, which is seemingly in a mood to throw its weight around because it doesn’t think much of India and its current leadership.

If the Indian government can suddenly demonetize the existing currency, and not worry even a bit about the inconvenience and scores of deaths in its wake, why can it not control population? This is India’s number one problem, and I can’t respect, or consider honest, any Indian leader who is not in favor of promulgating population control with equal vehemence.

The day Indians gain the ability to shun and shoo politicians who use caste, language, religion, river waters, gender, reservation, and other divisive vote bank tactics, is when India will have indeed won independence. That day India will be the Kohinoor of the world. It will be that precious golden sparrow it once was. Until then, my each heartbeat will hum the legendary words of Gurudev:

“Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Where knowledge is free

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments…

Into that heaven of freedom, my father, let my country awake.”

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.setumag.com on Sept 02 2017.

Representative picture of a dhaba.

Representative picture of a dhaba. Charanjeet’s Uncle

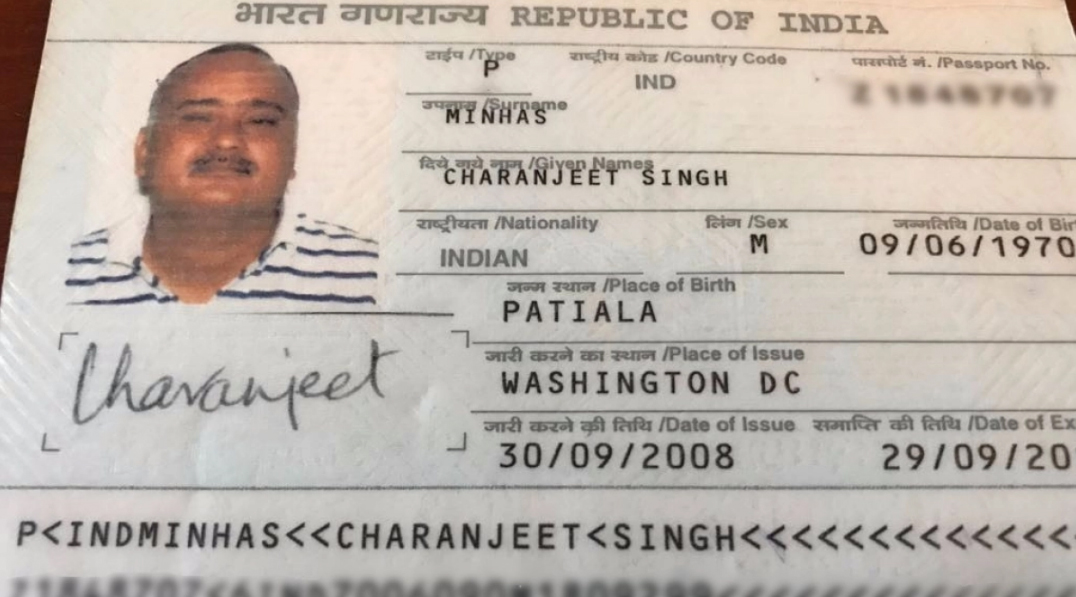

Charanjeet’s Uncle Charanjeet’s passport with a picture without beard and turban

Charanjeet’s passport with a picture without beard and turban

Recent Comments