by blogadmin | Jul 26, 2022 | Blog Post, India, Media Publishing's, Published Books, Punjabi Story, Sikhism, Story, Year 2022

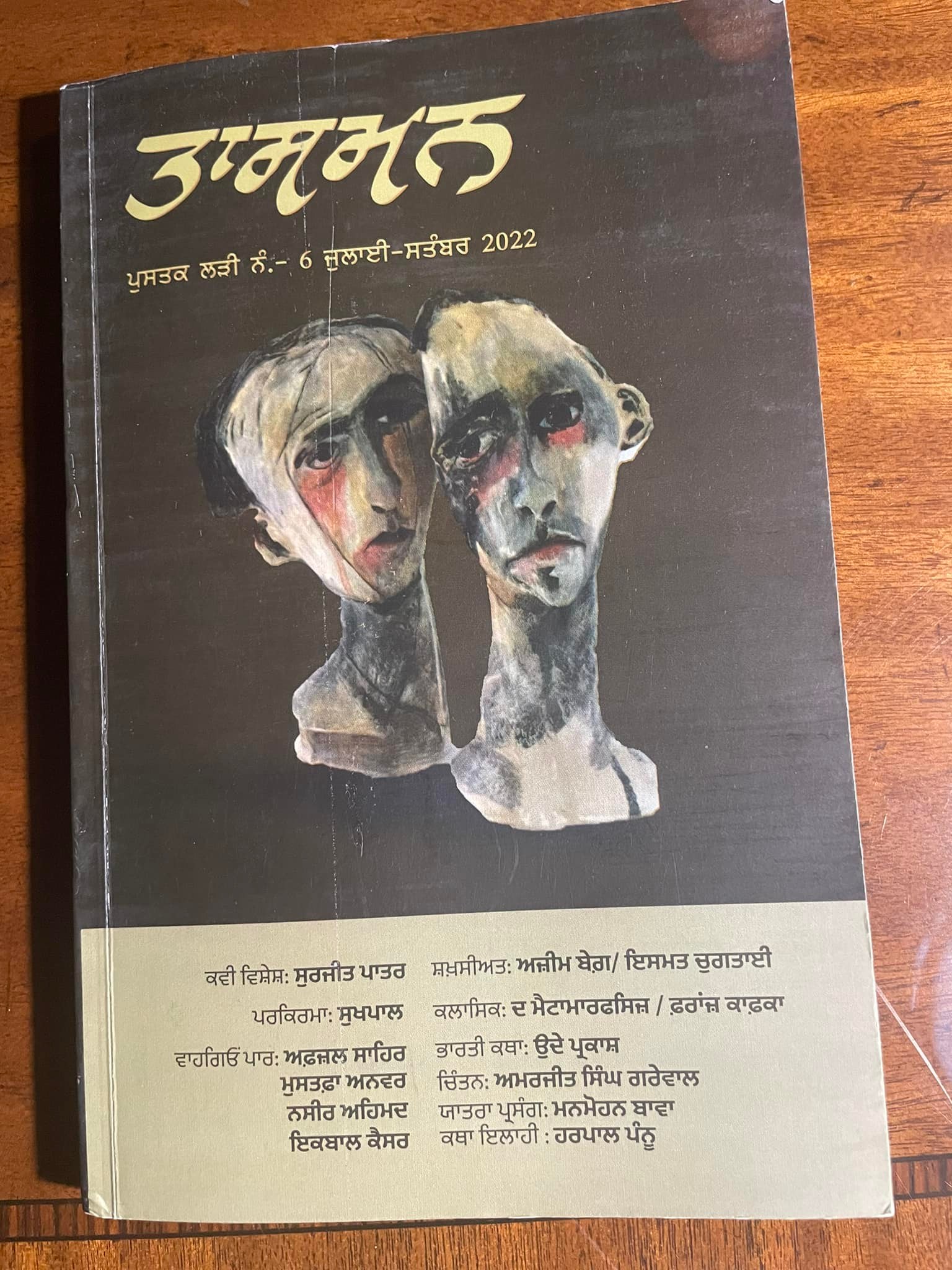

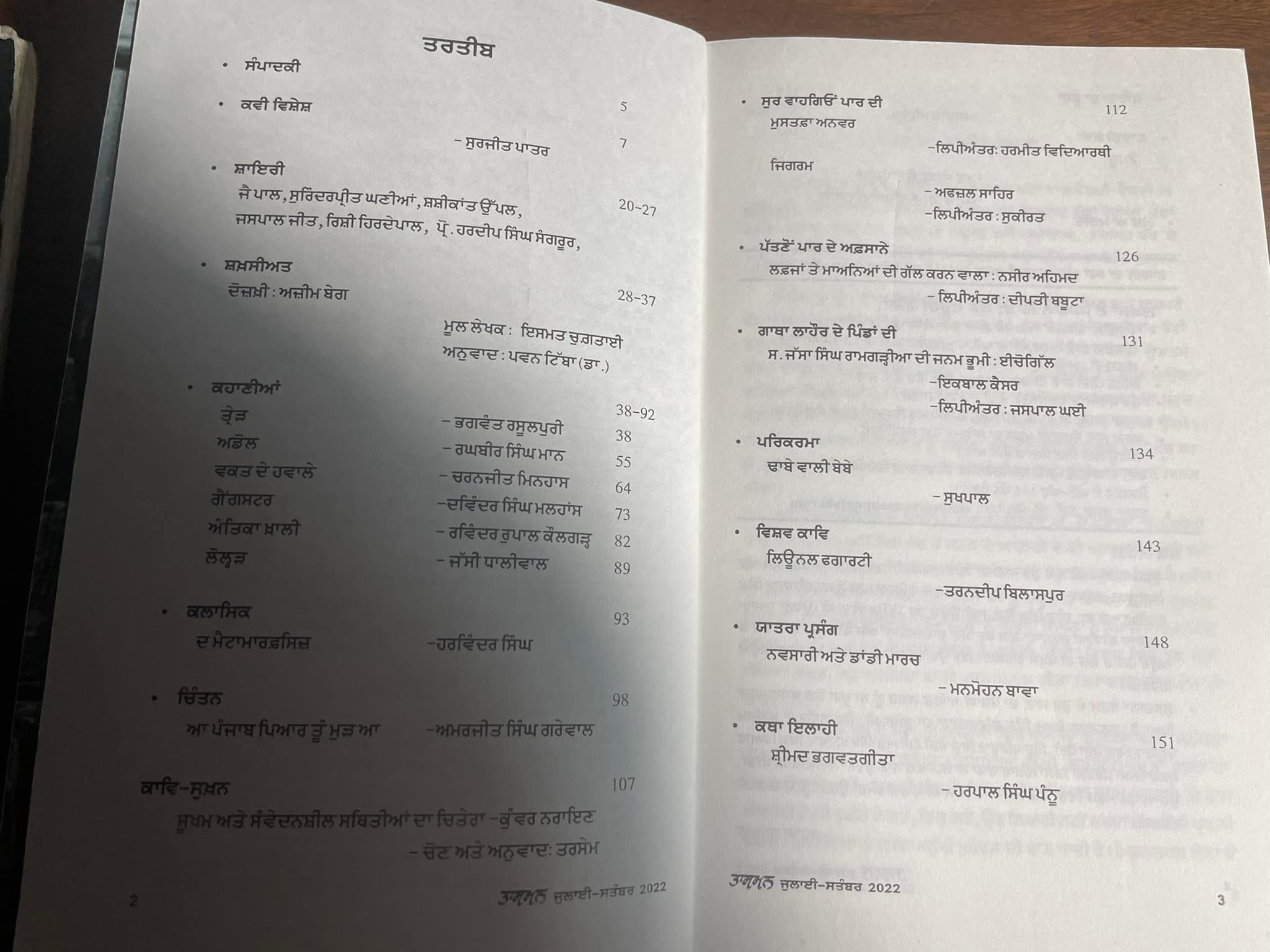

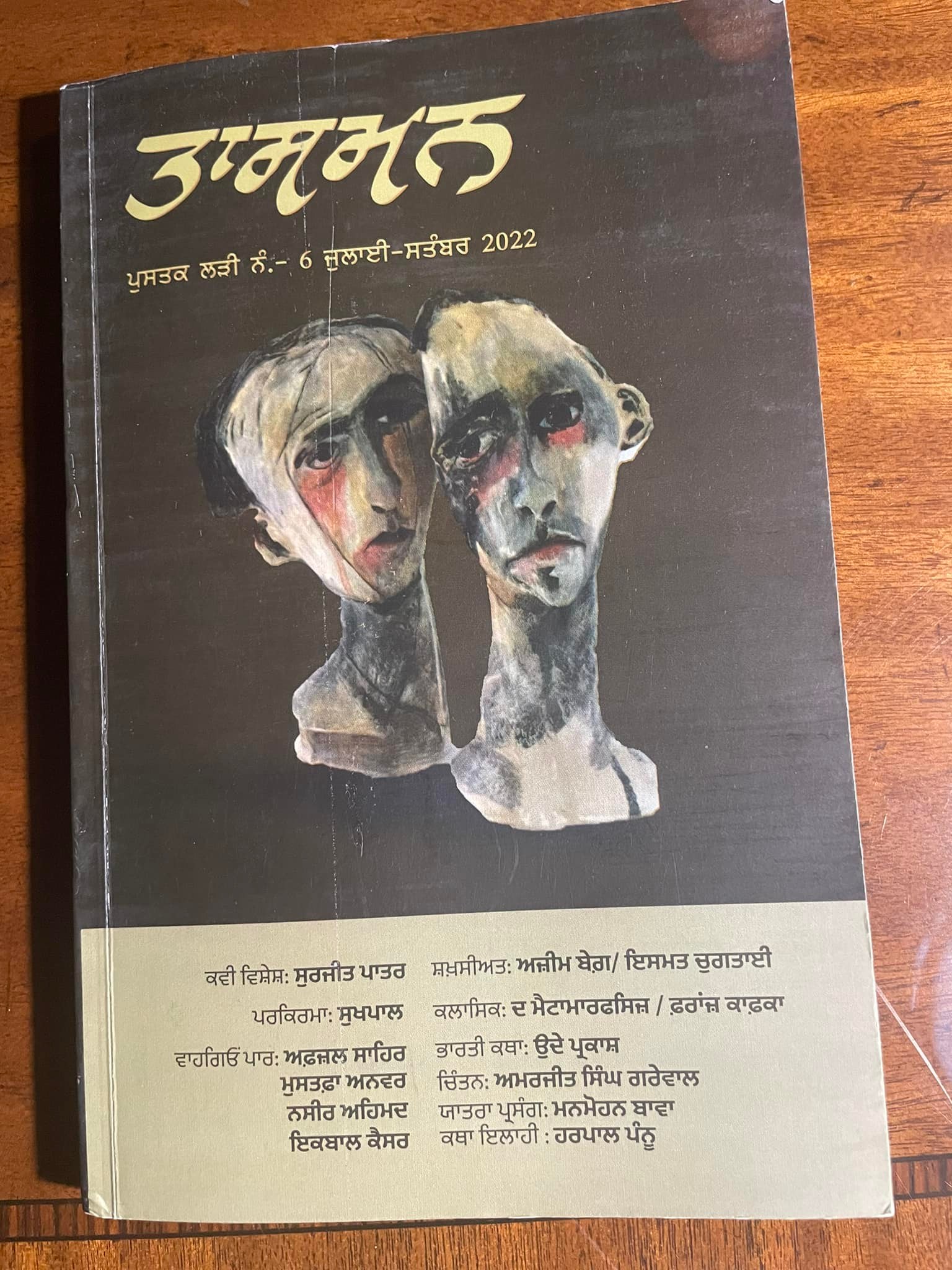

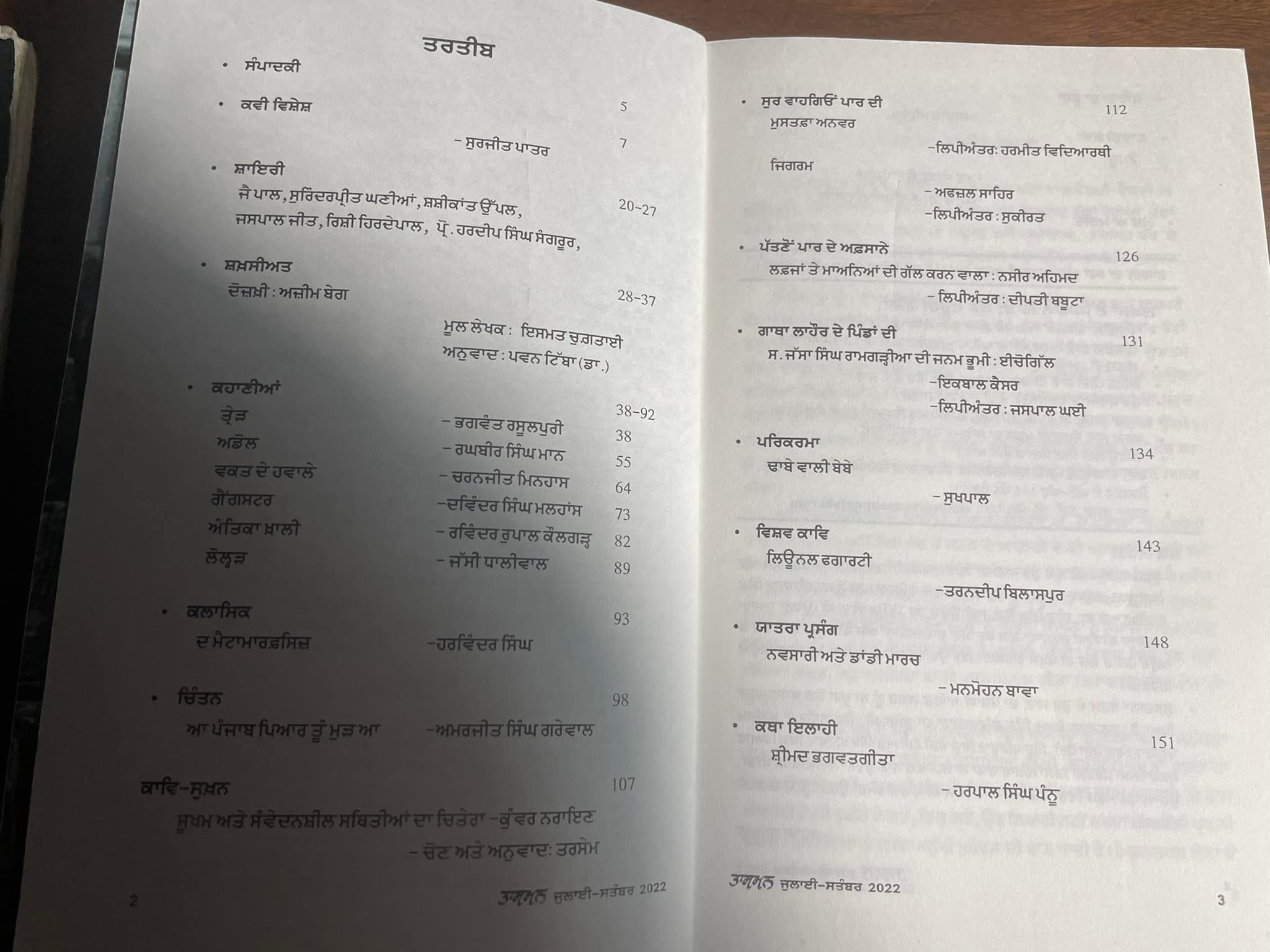

“Tasman” is a relatively new Punjabi quarterly magazine edited by Satpal Bhikhi—a poet of great repute. The magazine has earned name among the top literary publications of Punjabi.

It is my honor to have one of my stories published in its latest edition: No. 6, July-September 2022.

I am humbled to be alongside the greats of Punjabi literature.

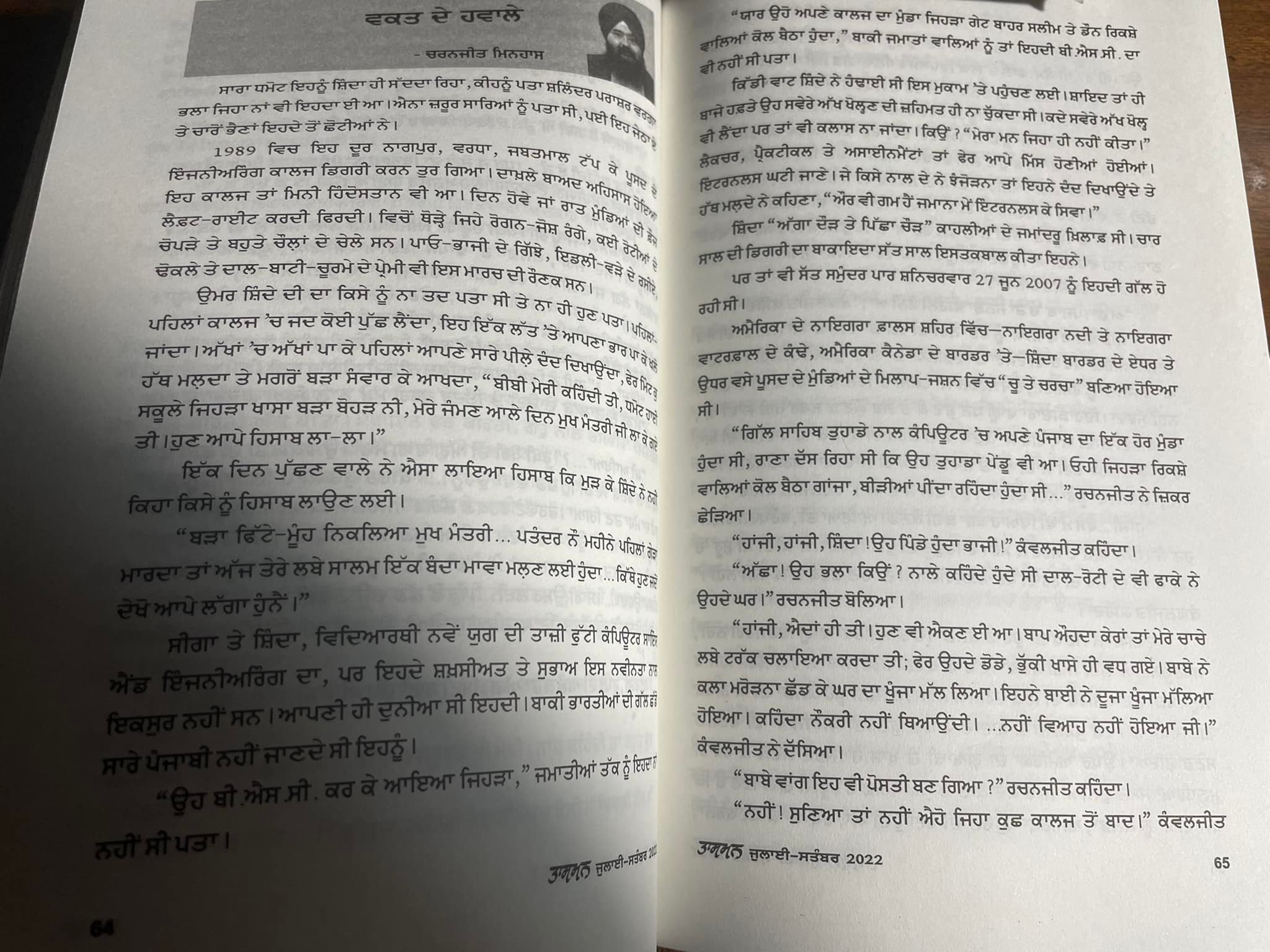

“Vakat De Havale” or “At the command of time” is a real life short story.

by blogadmin | Jul 26, 2022 | Blog Post, India, Media Publishing's, Published Books, Punjabi Story, Sikhism, Story, Year 2022

A short story authored by me is in the latest edition of Sirjana—one of the oldest and best literary magazines of Punjabi. An historic milestone in my writing pilgrimage.

by blogadmin | Nov 5, 2020 | Blog Post, Delaware, DSAC, Media Publishing's, Sikhism, Year 2020

Twenty-one years ago, when I came to America from India, I was amazed by its opportunities. Wasting no time, I started a software company that will celebrate its 22nd birthday next May. Doing business in the country was more straightforward, and accessibility to various institutions was much more comfortable than in India. However, when it came to how our president is elected, I still can’t say I have all the answers.

After a few years here, I realized that not everything between the two countries is different. Both are democracies, of course. More remarkable to me has been how America resembles India in look and spirit during their respective year-end holiday seasons. Homes, offices and markets in both countries are lit up during this period because of the different festivals and traditions each country celebrates.

For Halloween, Thanksgiving, Hannukah, Christmas and New Year’s Eve here during these weeks, India has Dussehra, Diwali, Bandi Chhor Diwas, Guru Nanak’s birth anniversary, Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Diwali is the greatest of them and celebrated nationally in October or November as per the dictates of the lunar calendar. It is celebrated on the same scale as Christmas in America and other Western countries.

Diwali is also called the “festival of lights,” and fireworks are an integral part of the celebration. Thanks to last year’s efforts and the initiative of Jay Muthukamatchi, it became possible for the first time in Delaware to buy and sell fireworks 30 days before every Diwali.

Halloween reminds me of Lohri (a bonfire celebration), which falls in the middle of January. Looking at boys and girls in the neighborhood going from door to door asking, “Trick or treat?” I recall my Lohri days as a young boy going with a group of other boys to various houses on my home street and adjoining lanes asking for “Lohri!”

The grand Annakut celebration at the BAPS Swaminarayan Mandir (Temple) in New Castle. During the celebration, there is an offering of different kinds of goods to God, accompanied by prayer. Annakut is part of the five day Diwali, or “Festival of Lights,” which coincides with the Hindu New Year and is celebrated around the world by millions of Hindus, Sikhs and Jains.

Neighborhood folks gave us cooked groundnuts and traditional Lohri sweets made from jaggery. It was incumbent upon those neighborhood houses to be extra generous in giving where a son’s wedding had recently happened, or they had been blessed with a male child. The gender bias has since largely passed, but unfortunately some of it still lingers on.

I am a Sikh. In Thanksgiving, I see the personification of Sarbat Da Bhala (prosperity, well-being, and glory of the whole universe) spirit. Every Sikh prayer, no matter what occasion, day, time, and place, ends with these three words: Sarbat Da Bhala.

I, too, said these words with everyone else because I had seen my parents, siblings, relatives and other Sikhs do the same. But I understood its essence only after arriving here in America and experiencing Thanksgiving and learning its background. To me, native Indians had enacted and personified the Sarbat Da Bhala’s underlying meaning in the Sikh prayer.

This year, while I am happy to see lights on neighbors’ houses and front yards, I can also see apprehension in many of their faces about what this election and the days and weeks following it will bring. Maybe the lights are illuminating the darkness convulsing our hearts and minds ravaged by the soaring coronavirus numbers, historic unemployment, increasing pain and suffering of the poor and vulnerable, and divisions like never before among this country’s various communities.

Regardless of whether America retains Trump or sends our Delaware’s Joe Biden to the White House, I want and wish that there be a light for everyone in the embrace of hope and peace.

Delaware Air National Guard Adjutant General Carol Timmons (center left) speaks with Charanjeet Singh Minhas of the Delaware Sikh Awareness Coalition at a Thanksgiving prayer breakfast.

Fortunately, I know of many ordinary Delawareans doing extraordinary work toward that goal: veterans in the Interfaith Veterans Workshop group founded by Rev. Tom Davis; members in my writing group, Brandywine Writers Circle, founded and led by Joan Leof; and a host of others — pastors, imams, rabbis, Hindu and Sikh priests in Delaware — who are part of efforts to spread love and peace and defeat hatred and violence.

They are all — in their languages, in their traditions, in their own homes or their places of worship, in their own words and ways — praying for Sarbat Da Bhala.

by blogadmin | Jan 26, 2020 | Blog Post, Delaware, Media Publishing's, Sikhism, Year 2020

I am a Sikh.

A turban is an article of faith for the Sikhs. It signals honesty, service and compassion to those in need. But the opposite has been perceived in our country, especially after 2001.

Many of my fellow Americans continue to mistake Sikhs for those they aren’t, simply because of their appearance.

From bullying in schools to discrimination in the workplace to becoming victims of violence, Sikhs continue to suffer because fellow citizens connect their appearance to terrorism.

As a result, more and more Sikhs are practicing their faith without its most visible article — the turban and the unshorn hair under it.

The first American killed by a fellow citizen in vengeance after 9/11 was a turbaned Sikh in Mesa, Arizona on Sept. 15, 2001.

Last September, in Texas, a routine traffic stop cost turbaned deputy Sandeep Dhaliwal his life. Another turbaned Sikh in Tracy, California, Paramjit Singh, was stabbed to death during a routine walk in the park last August. The list of such brutalities against turbaned Sikhs goes on.

Even America’s largest employer, the military, for decades did not allow Sikhs to serve with their articles of faith despite their rich and proud warrior history and inspiring record of service in the armed forces of various countries. More than 80,000 Sikh soldiers laid down their lives serving alongside Allied forces during World Wars I and II.

In 2017, after years of lawsuits and pressure, the U.S. Army changed its policy to allow observant Sikhs and members of other religions to wear beards and head coverings provided permission is applied for in advance. The NYPD now allows Sikh officers to wear turbans, joining a few other local law enforcement agencies with similar policies.

Yet, while some Sikhs have fought long and hard for the right to wear the turban, others have voluntarily abandoned this tradition, perhaps because of its possible impact on their personal or professional lives.

For example, here in Delaware, there are several prominent Sikh doctors but not one who wears a turban — despite their towering presence on the trustee and management boards of the state’s two gurdwaras, which are Sikh temples.

For Sikh women, life is easier on this count because a turban is optional for them. However, even without a turban, belonging to the Sikh faith or having brown skin can impede or even disqualify their participation in mainstream activities.

This is something Nikki Haley (nee Nimrata Nikki Randhawa), former governor of South Carolina and U. S. Ambassador to the United Nations, reportedly learned in her hometown of Bamberg, South Carolina, when she was 5.

Nikki’s parents had attempted to enter her in the “Miss Bamberg” contest but her application was rejected because she did not qualify for either crown: black or white. Eventually, a few years before entering politics, she changed her religion from Sikhism to Christianity.

It is ironic that in some parts of the world, the turban is viewed as a sign of security, not a threat. In India, the Sikh homeland, a single woman, or anyone who feels insecure, is more likely to hire a turbaned Sikh driver because of their well-known dedication to serving the needy and protecting the weak and vulnerable.

So in 2020 and beyond, how can Sikhs and other religious groups correct the misconceptions that appearances generate in those who are ignorant, hateful and impulsive?

Only through education and participation in schools, workplaces, houses of worship and communities — and a strong media presence — can observant Sikhs encourage and expect understanding.

Let’s hope that someday all Sikhs can base their decision to wear or not wear a turban purely on personal choice and not on external influences or threats.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.delawareonline.com on January 24, 2020.

by blogadmin | Nov 11, 2019 | Blog Post, Media Publishing's, Sikhism, Year 2019

A few months ago, my wife and I decided to do the unthinkable: visit Pakistan.

Before boarding the Philadelphia-Lahore flight last month, I wrote an op-ed for Pakistan’s The Daily Times, but never anticipated the reaction on social media. Some of my fellow Indians — not only Modi devotees — were offended by my positive mentions of Pakistan and Muslims. The Patel community was most upset.

With this uncertain start, how could we believe that our maiden Pakistan visit would be such a joyous experience? From the moment we arrived we were treated like celebrities. Shopkeepers and restaurants would first refuse to accept money.

It is important to mention here that I was in a country and among people I had done my best all these years to avoid.

This side of Punjab has a lot of camels. I also observed rampant pigeon grooming for gambling. In Faisalabad (old Lyallpur), I was awestruck to see its sky blanketed by colourful kites. The city’s Gobind Pura, Nanak Pura and Harcharan Pura show its inseparable Sikh connection.

When we arrived at Lyallpur Khalsa College (now Municipal Degree College) on a late Friday afternoon, the college appeared to be closed. The security guard pointed us towards the principal who was just opening his car door. One of our local companions hurriedly approached the principal. I will never forget the principal’s words: ‘It is their college, their property. They built it. Who am I to give them permission to tour it?’

Pakistani Punjabi has always been endearing to me, even though my friends and I often made it a butt of our jokes. That its speakers found my Punjabi interesting and original was a pleasant surprise.

Outside Lahore’s Defence Raya Golf and Country Club, I was introduced to Lt Gen Zahid Ali Akbar (retd). Although 88 years of age, he seemed fit enough to finish a marathon. ‘What a joy to speak real Punjabi with you. What they speak here isn’t Punjabi. Teach them some before you leave!’ he said, pointing to my hosts.

At the Punjab Club, Lahore’s colonial hangover is unmistakable. Its dress code and no-photo policy are non-negotiable. Thanks to an invitation from Riaz Ahmad Khan, retired chief justice of the Pakistan Supreme Court, and his wife, we were allowed to visit and eat there.

It was a remarkable journey. I have lived in England as a student and visited many European and Central American countries for business and leisure. I have seen more expansive physical beauty and natural diversity, awe-inspiring infrastructure and impeccable systems. However, never before have I seen such hearty hospitality or experienced an abundance of love that so contrasted with a country’s image abroad. No wonder that we frequently asked each other, ‘Are we in Pakistan?’

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.tribuneindia.com on November 09, 2019.

by blogadmin | Nov 5, 2019 | Blog Post, Media Publishing's, Sikhism, Year 2019

In an October 5, 2019 column, I wrote about the overwhelming support and love my wife Harpreet Minhas and I received from Delaware’s Pakistani community in America on learning that we were travelling to Pakistan for the first time.

Guru Nanak’s 550th birth anniversary had inspired us to make the trip-one we had previously thought impossible. As it turned out, the eight days I spent in the country so feared by many turned out to be eight of my best.

Our Qatar flight on October 23 had landed almost an hour earlier in Lahore, just past midnight. Immigration and customs were a breeze-a pleasant surprise because getting our Pakistan visas in Washington D.C. had taken us a month.

The airport’s infrastructure and overall condition reminded me of India’s Nagpur airport, which I had visited before coming to America in 1999.

Outside, our trip guide and facilitator, Irfan Raza-our Delaware friend Rubina Malik’s relative and our ride to the Pearl Continental Hotel-had not yet arrived.

Walking around, I started looking and observing and taking pictures of my first glimpses of the Lahore I had read and heard so much about. A Sikh anywhere in the world has a special bond with Lahore for historical, religious, cultural and language reasons.

A bit later, a tall, good-looking man approached me. “Sat Sri Akal Ji.”

“Sat…Sri…Akal,” I mumbled, trying hard to place this familiar face.

Is he one of my wife’s many cousins who live in the Jalandhar belt or a sibling of one of my hometown Patiala friends? His smile and sweet and friendly demeanor provided no clues.

“Sorry, you are…?”

“Irfan, Ji.”His face bloomed even more as he stretched out his right hand. His beautiful wife, Bushra, stood by his side clasping her hands like I do many times when in a gurdwara.

Before they left after checking us in the hotel, we discussed how to overcome various uncertainties we may face arising from Maulana Fazlur Rehman’s call for nationwide protests. We decided to mitigate possible risks by visiting destinations outside Lahore first.

As planned, after we had bathed, changed, slept a few hours and eaten, Irfan and Bushra picked us up to go to Gurdwara Janam Asthan in Nankana Sahib. Irfan was driving.

We headed west and soon reached a bridge over a dry riverbed.

“India stopped Ravi’s water,” Irfan said, anticipating my question.

The dehydrated Ravi illustrated the rocks and stones and ravines in India and Pakistan relations. In my heart I asked Guru Nanak, “Will there be a day when these two neighbours will drown their rocks and stones and flow together in peace and harmony?”

After about three hours we reached the gurdwara on the site where 550 years earlier Guru Nanak Dev was born. I entered the compound and continued to walk towards the gurdwara. A man in his sixties, coming from the opposite side, greeted me.

“I am Abdul Rasheed. My elders revered Baba Nanak. Baba Fareed is our saint; he and Nanak are the same, they taught us. Sardarji, you are fortunate that he has summoned you to his darbar.”

Abdul’s wear was simple and his manner rustic, but what he said was divine.

“This is my first time. Do you live here in Nankana Sahib?” I asked.

“No, Samundari, near Lyallpur. This is my first time as well, though I have been intending to visit for decades.”

“Ah! Because it is his 550th, that’s why you came as I did from America?”

“No, I didn’t know it. Bhaiji (Sikh priest) inside, who fed us food, water and tea, told us. Sardarji, you came because he sent for you. I came because he called me, and he called me now. How could I come before?”

With that, he walked away quietly humming something.

When I came out after paying my obeisance, a group of seven non-Sikh men asked me for a picture. Another family requested the same when we were collecting our shoes.

Such requests for pictures by men and women, boys and girls, individuals and families, young and old, on foot or a bike or in a car grew in the days ahead. Why was I such a celebrity? Honestly, I don’t know.

For instance, the next day, before we reached Kartarpur Sahib, a camel owner in Narowal asked me for a picture. On arrival in the compound of the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib, we were mobbed by the national and international media present there rafter covering the signing of the agreement between India and Pakistan to operationalise Kartarpur Corridor. In Faisalabad, on Friday, visiting Lyallpur Khalsa College (now Municipal Degree College) was one of our top priorities. When we reached its gate, the college appeared to be closed and the helpless security guard pointed us towards the principal about to leave in his car.

When Aslam from our local host group approached him, I will never forget his reply: “It is their college, their property. They built it. Who am I to give them permission?”

Other than absent bars and wine shops and Urdu street signs, it is difficult to tell the two Punjabs apart. East Punjab doesn’t have a large and developed city like Lahore, soaked in grand history. Its DHA developments may have no match in northern India, while the Packages Mall could be a shopping destination anywhere on the globe.

I have lived in England as a student and visited many European, North, South and Central American countries for business and leisure. Australia and Asia as well. I have seen more expansive physical beauty and natural diversity, awe-inspiring infrastructure and impeccable systems.

However, never before have I seen such hearty hospitality or experienced an abundance of love that so contrasted with a country’s image abroad. No wonder that Harpreet and I frequently asked each other, “Are we in Pakistan?”

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by the www.dailytimes.com.pk on November 05, 2019.

Recent Comments