Back in Mammaji’s hospital room, there were always a couple of folks from his village visiting him.

I, who had prided myself on retaining some of my Punjabi rusticity irrespective of the time I sepnt away from my watan, could relate to much of what Mammaji’sfriends and relatives spoke about. But a couple of days into my visit, I heard a story that shook me up.

It was about an older cousin’s son. I hadn’t met or spoken to this cousin in years, son of yet another Mammaji who passed away long ago. He lives next door to the ailing Mammaji in the same village.

This cousin’s son had apparently got obsessed with a girl who was visiting the village from a nearby district to attend a family wedding. These wedding visits can last a few weeks. So he had had the time for this obsession to develop and grow.

I was told that the amourous charges kickstarted a pattern of stalking the girl and her friends, or simply leering at her. He and a small bunch of his friends made these ogling sessions a daily habit.

Elders in the village either indulged these young men, or saw nothing wrong in what they were doing quite openly. There was no reprimand. Not that the youngster needed it. They were adults, supposed to possess their own moral compass and have a certain fear of the law as well. But no. The story took a turn for the horrific.

A short while after the girl returned to her village, a group of these youngsters, my cousin’s son included, allegedly gangraped her at her home.

And the story doesn’t end here.

Soon after, not only did these men get bail after spending some time in jail, my cousin’s son, I was told, was soon engaged to another, with the wedding scheduled for later this winter. That’s how much acceptability a man accused of rape has in Indian society today.

Sure, the law says these men are not guilty until convicted. But there was a well-known history of stalking, of these men singling out that girl for their attention.

Surely, the family into which my cousin’s son would be marrying, was aware of this recent history. And yet, they were willing to push a girl from their family to spend a lifetime with such a person.

It would be silly for me to say that I wasn’t aware of other such stories. I read them in the papers when I’m here in India, I read about them on news websites when I’m in the US. But this was happening almost within immediate family.

So it shook me up a whole lot more. Suddenly, I wanted no part of this. The absence of all morality, the absence of basic respect for women, the absence of the rule of law, that allowed hooligans and perverts to run amok here. I wanted no part of it.

I was reminded of the liquor I acquired with such ease at the dhaba. Illegal again. Did this gang also prime themselves for their horrific act with some illegally purchased liquor at a similar dhaba? It bothered me that I too had ignored the law to have that drink that night.

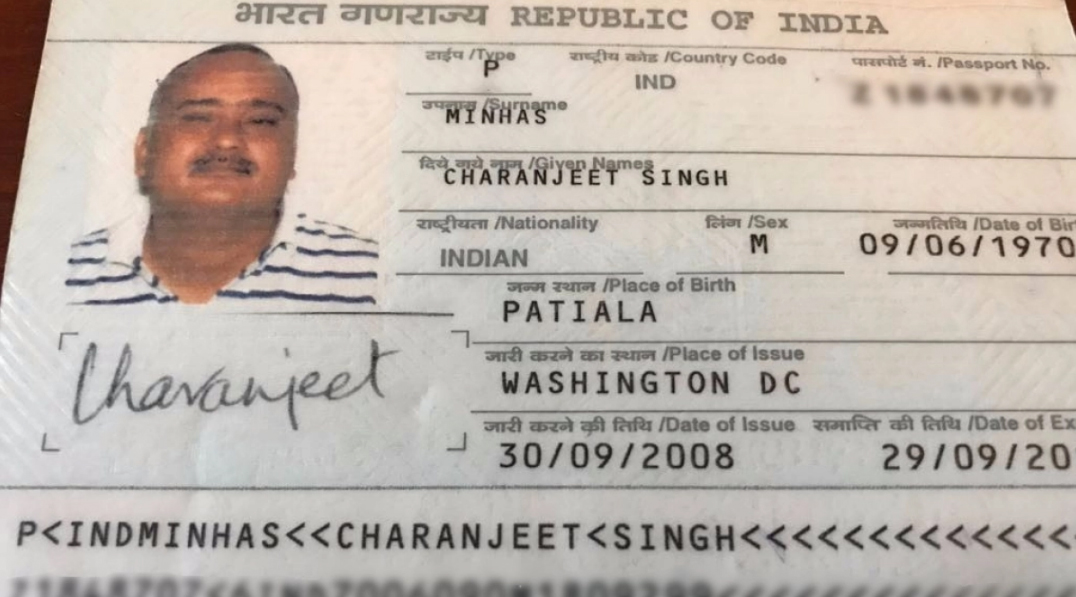

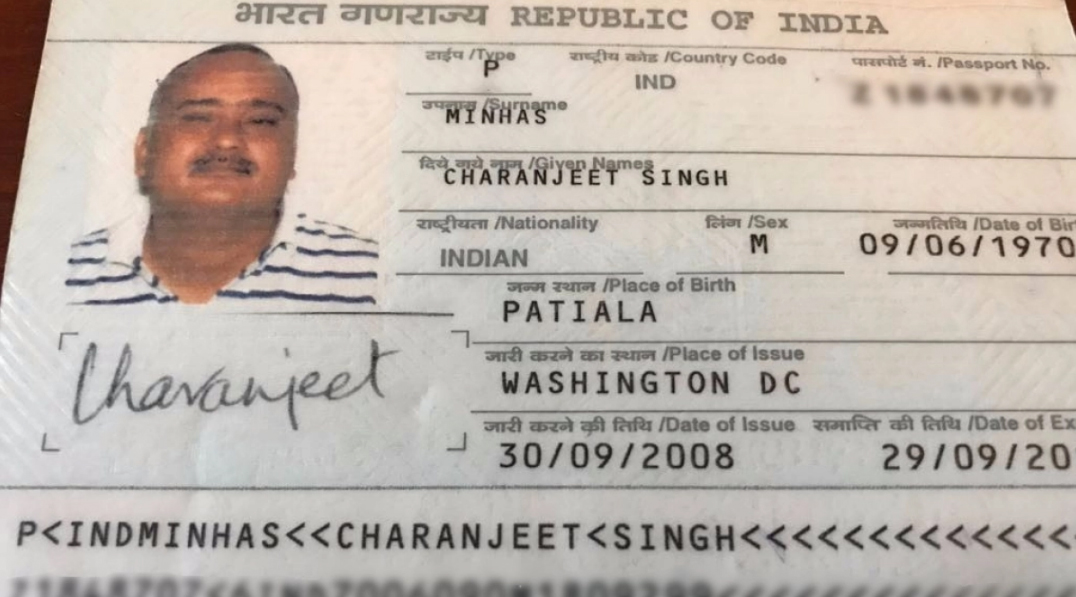

Charanjeet’s passport with a picture without beard and turban

Charanjeet’s passport with a picture without beard and turban

The Straw That Broke the Camel’s Back

My return flight, AI 127, was scheduled for 2:20 am a few nights later. Force of habit saw me at Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport four hours before the scheduled departure. Check-in was smooth and swift.

I headed next toward the immigration section, one last bureaucratic spin before departure. When my turn came, I walked up to the officer, greeted him, and gave him my passports — old, expired, and current joined together — along with my US permanent resident card (green card).

He looked at the picture in my current passport issued in 2008 and then at me. “From where and why did you acquire this beard and turban?” he asked sternly. In the picture on the passport, I sported neither. “Meri marzi se ji,” I said smiling.

“What? Is this how you talk to Government of India?” I was stunned. What was his problem and why was he being so rude?

“How would you want me to speak and what else can I say, apart from the truth?” I said as politely as possible and volunteered to cooperate in every way if he wished to further ascertain my identity.

My green card has the current picture, and so do my US and India driver licenses, I told the officer.

I had also gone in and out of India quite a few times in exactly the same manner, with the same look. No questions asked.

The man just kept turning the pages of my passport. Then he opened the old passport and pointing to the picture, asked, “Is that you?” “Yes, in the good old days, ji,” I said, smiling in an attempt to lighten the situation. Still more squinting at me, and back at the passports.

I don’t know, maybe he was waiting for me to say something he wanted to hear. Confess to something? When that didn’t happen, he looked at me menacingly one last time, got off his seat, and disappeared.

When he returned, there were other officers with him. One of them, possibly a higher authority, went through my papers yet again, and asked, “Why didn’t you change your picture?”

“The passport is still current. It will be up for renewal next year and I will do it then,” I explained. “Don’t wait till then. Do it as soon as you can,” he advised. He wasn’t rude. “Advice appreciated,” I told him. “I will do it as soon as I have an opportunity, ji”

I reached home. Of course, the US has now been home for years, but I felt it a lot more for the first time then.

Normally, this psychological feeling of having a part of me planted here and another in India, has not been hard to handle. I had run my software testing business originally from the US, but later added a branch at Bangalore as well. I had shut down the Bangalore end after 10 years, beaten down by red tape. Even that had not dampened my affection for my watan.

But, something did change within me during this visit that lasted less than a week. The intangible umbilical cord got cut, and I’ve finally gone ahead and applied for my new Amriki passport.

– – – – – – –

This column was published online by www.thequint.com on March 20.

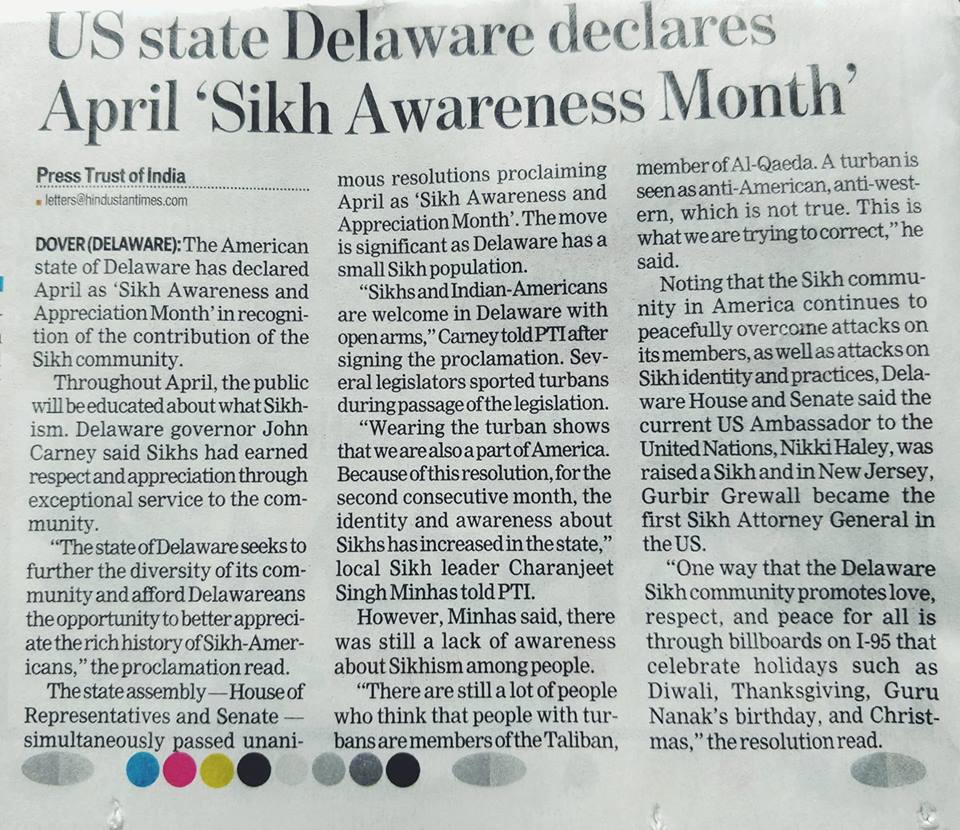

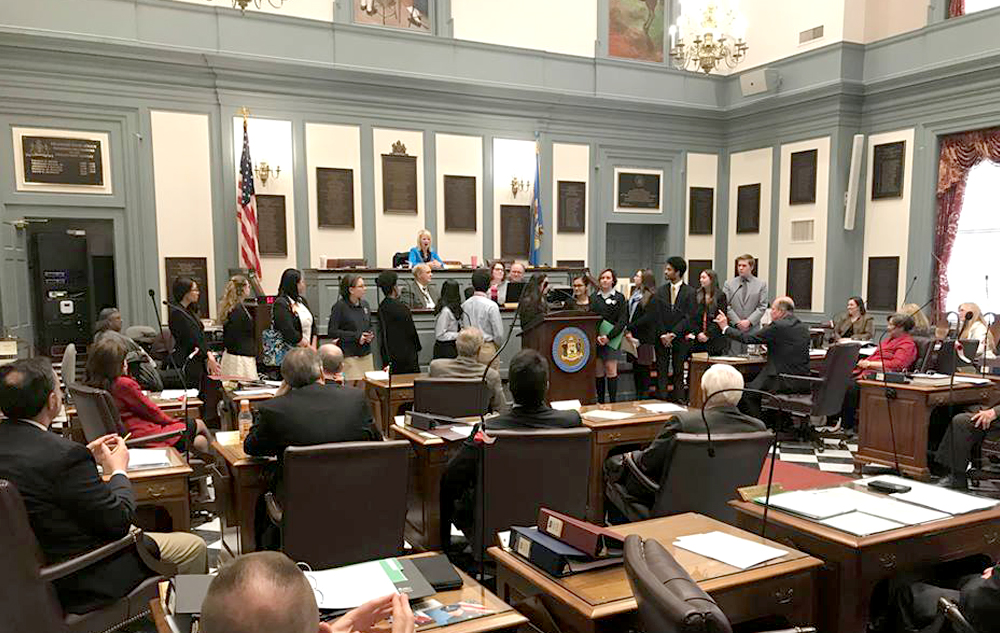

On March 27, 2018 HCR 67 proclaimed April 2018, “Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month” in Delaware. Our big thanks to our dear friends Representative Paul Baumbach who first introduced the resolution in the House and Senator Bryan Townsend who later introduced it in the Senate. It was unanimously passed in both the chambers.

On March 27, 2018 HCR 67 proclaimed April 2018, “Sikh Awareness and Appreciation Month” in Delaware. Our big thanks to our dear friends Representative Paul Baumbach who first introduced the resolution in the House and Senator Bryan Townsend who later introduced it in the Senate. It was unanimously passed in both the chambers.

In 2018 Vaisakhi, the grand day for Sikhs worldwide, is on Saturday, April 14. Like fragrance and flower are inseparable, good and great things also hold hands. April 14 is also “National Reach as High as You Can Day”.

In 2018 Vaisakhi, the grand day for Sikhs worldwide, is on Saturday, April 14. Like fragrance and flower are inseparable, good and great things also hold hands. April 14 is also “National Reach as High as You Can Day”.

Representative picture of a dhaba.

Representative picture of a dhaba. Charanjeet’s Uncle

Charanjeet’s Uncle Charanjeet’s passport with a picture without beard and turban

Charanjeet’s passport with a picture without beard and turban

Recent Comments